vcmi-gym

An AI for the game of "Heroes of Might and Magic III"

You must have heard about Heroes of Might and Magic III - a game about strategy and tactics where you gather resources, build cities, manage armies, explore the map and fight battles in an effort to defeat your opponents. The game is simply awesome and has earned a very special place in my heart.

If you know, you know :)

Released back in 1999, it’s still praised by a huge community of fans that keeps creating new game content, expansion sets, gameplay mods, HD remakes and whatnot. That’s where VCMI comes in: a fan-made open-source recreation of HOMM3’s engine ❤️ As soon as I heard about it, my eyes sparkled and I knew what my next project was going to be: an AI for HOMM3.

Problem Statement

The game features scripted AI opponents which are not good at playing the game and are no match for an experienced human player. To compensate for that, the AI is cheating - i.e. starts with more resources, higher-quality fighting units, fully revealed adventure map, etc. Pretty lame.

Objective

Create a non-cheating AI that is better at playing the game.

Proposed Solution

Transform VCMI into a reinforcement learning environment and forge an AI which meets the objective.

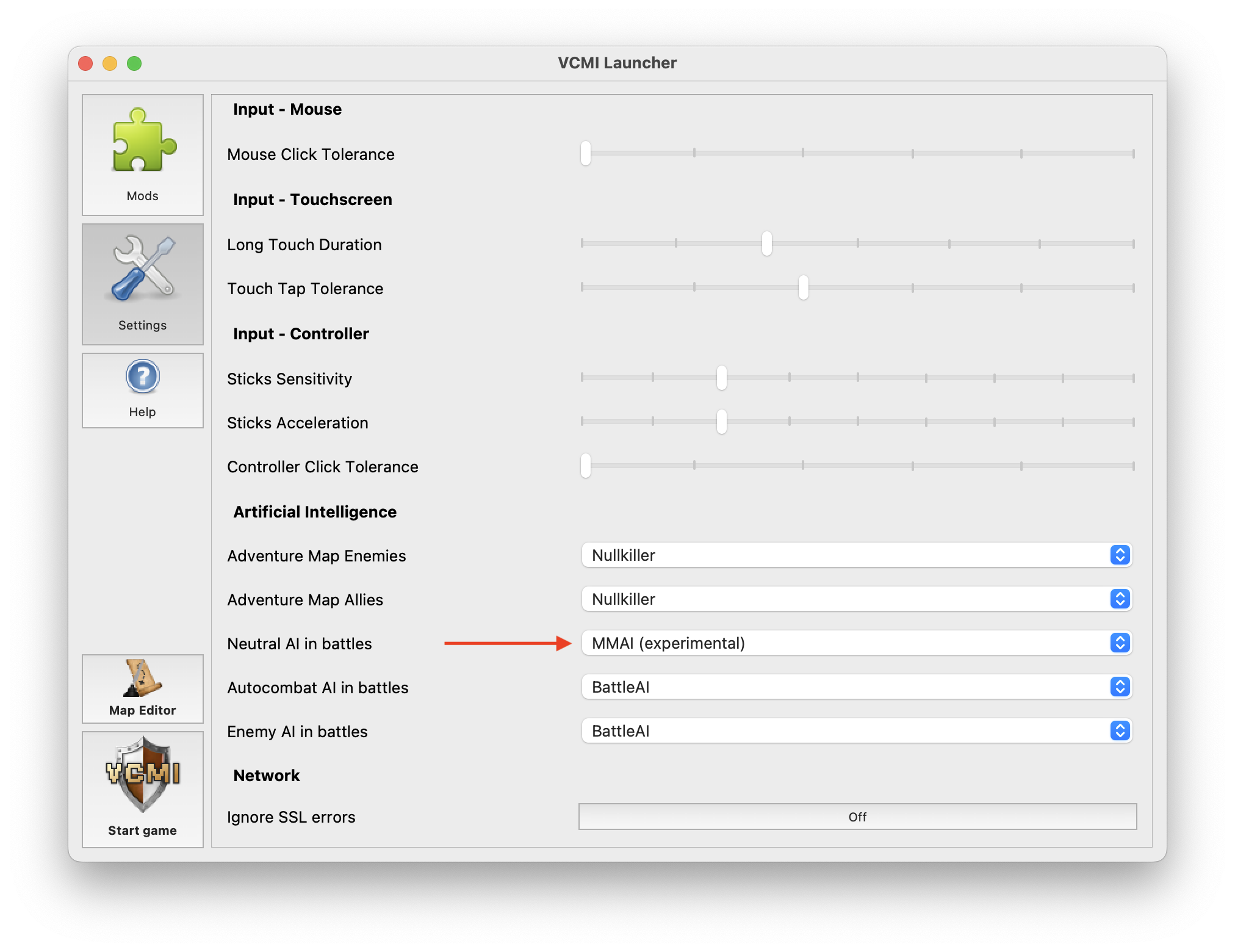

Contribute to the VCMI project by submitting the pre-trained AI model along with a minimal set of code changes needed for adding an option to enable it via the UI.

Approach

Given that the game consists of several distinct player perspectives (combat, adventure map, town and hero management), training separate AI models for each of them, starting with the simplest one, seems like a good approach.

Phase 1: Preparation

- Explore VCMI’s codebase

- gather available documentation

- read, set-up project locally & debug

- if needed, reach out to VCMI’s maintainers

- document as much as possible along the way

- Research how to interact with VCMI (C++) from the RL env (Python)

- best-case scenario: load C++ libraries into Python and call C++ functions directly

- fallback scenario: launch C++ binaries as Python sub-processes and use inter-process communication mechanisms to simulate function calls

Phase 2: Battle-only AI

- Create a VCMI battle-only RL environment

- follow the Farama Gymnasium (ex. OpenAI Gym) API standard

- optimise VCMI w.r.t. performance (e.g. no UI, fast restarts, etc.)

- Train a battle-only AI model

- observation design: find the optimal amount of data to extract for at each timestep

- reward design: find the optimal reward (or punishment) at each timestep

- train/test data: generate a large and diverse data set (maps, army compositions) to prevent overfitting.

- start by training against the VCMI scripted AI, then gradually introduce self-training by training vs older versions of the model itself. Optionally, develop a MARL (multi-agent RL) where two two agents are trained concurrently.

- observability: use W&B and Tensorboard to monitor the training performance

- Bundle the pre-trained model into a VCMI mod called “MMAI” which replaces VCMI’s default battle AI

- Contribute to the VCMI project by submitting the MMAI plugin along with the minimal set of changes to the VCMI core needed by the plugin

- Contribute to the Gymnasium project by submitting vcmi-gym as an official third-party RL environment

Phase 3: Adventure-only AI

Worthy of a separate project on its own, training an Adventure AI is out of scope for now. A detailed action plan is not yet required.

Dev journal

I will be outlining parts of the project’s development lifecycle, focusing on those that seemed most impactful.

Since I started this project back in 2023, there will be features in VCMI (and vcmi-gym) that were either introduced, changed or removed since then, as both are actively evolving. Still, most of what is written here should be pretty much accurate for at least a few years time.

Setting up VCMI

First things first - I needed to start VCMI locally in debug mode. Thankfully, the VCMI devs have provided a nice guide for that. Some extra steps were needed in my case (most notably due to Qt installation errors), for which I decide to prepare a step-by-step vcmi-gym setup guide in the project’s official git page. the installation notes below:

Except for a few hiccups, the process of setting up VCMI went smooth. It was educational and gave me some basic, but useful knowledge:

- CMake is a tool for compiling many C++ source files with a single cmake command. A must for any project consisting of more than a few source files.

-

conanis likepipfor C++ - Debugging C++ code can be done in many different ways, so I made sure to experiment with a few of them:

-

lldbcan be used directly as a command-line debugging tool. I feel quite comfortable with CLIs and I looked forward to using this one, but the learning curve was a bit steep for me, so opted for a GUI this time. - Sublime Text’s C++ debugger was a disappointment. I am a huge fan of ST and consider it the best text editor out there, but it’s simply not good for debugging.

- VSCode’s debugger really saved the day. Has some glitches, but is really easy to work with. I will always prefer ST over VSC, but I do have it installed at all times, just for its debugger capabilities.

- Xcode did not work well. VCMI is not a project that does not follow many Xcode conventions (naming, file/directory structure, etc.) which made it hard to simply navigate through the codebase. Well, IDEs have never felt comfortable anyway, so there was no need to waste my time further here.

-

- C++ language feature support (completions, linting, navigation, etc.) in Sublime Text 4 is provided by the LSP-clangd package and is awesome. I found it vastly superior to VSCode’s buggy C++ extension.

Unfortunately, VCMI’s dev setup guide was like a nice welcome-drink on a party where nothing else is included. That’s to say, there was no useful documentation for me beyond that point. No surprises here - I’ve worked on enough projects where keeping it all documented is a hopeless endeavor, so I don’t blame anyone. My hope is that the code is well-structured and easy to understand. Good luck with that - the codebase is over 300K lines of C++ code.

So… how does it work?

Having it up & running, it was time to delve into the nitty-gritty of the VCMI internals and start connecting the dots.

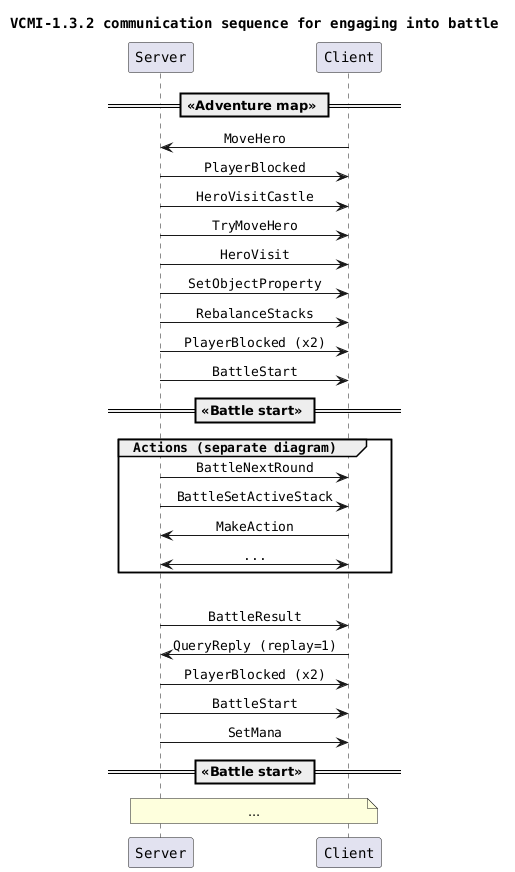

VCMI’s client-server communication protocol

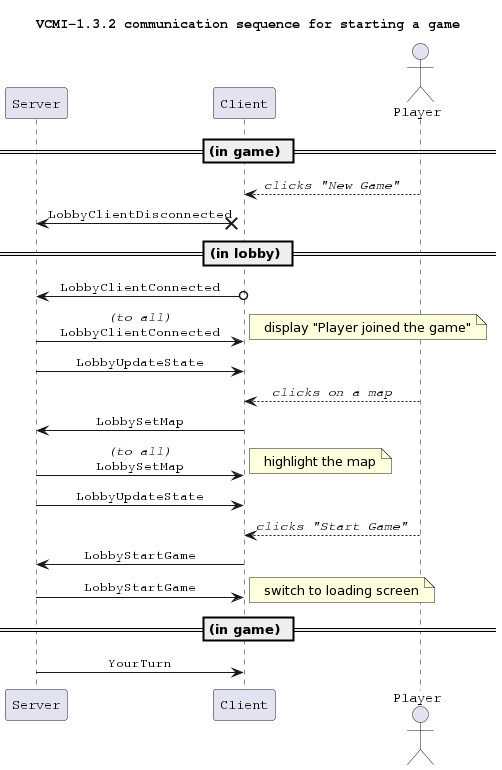

The big picture is a classic client-server model with a single server (owner of the global game state) and many clients (user interfaces).

Communication is achieved via TCP where the application data packets are serialized versions of CPack objects, for example:

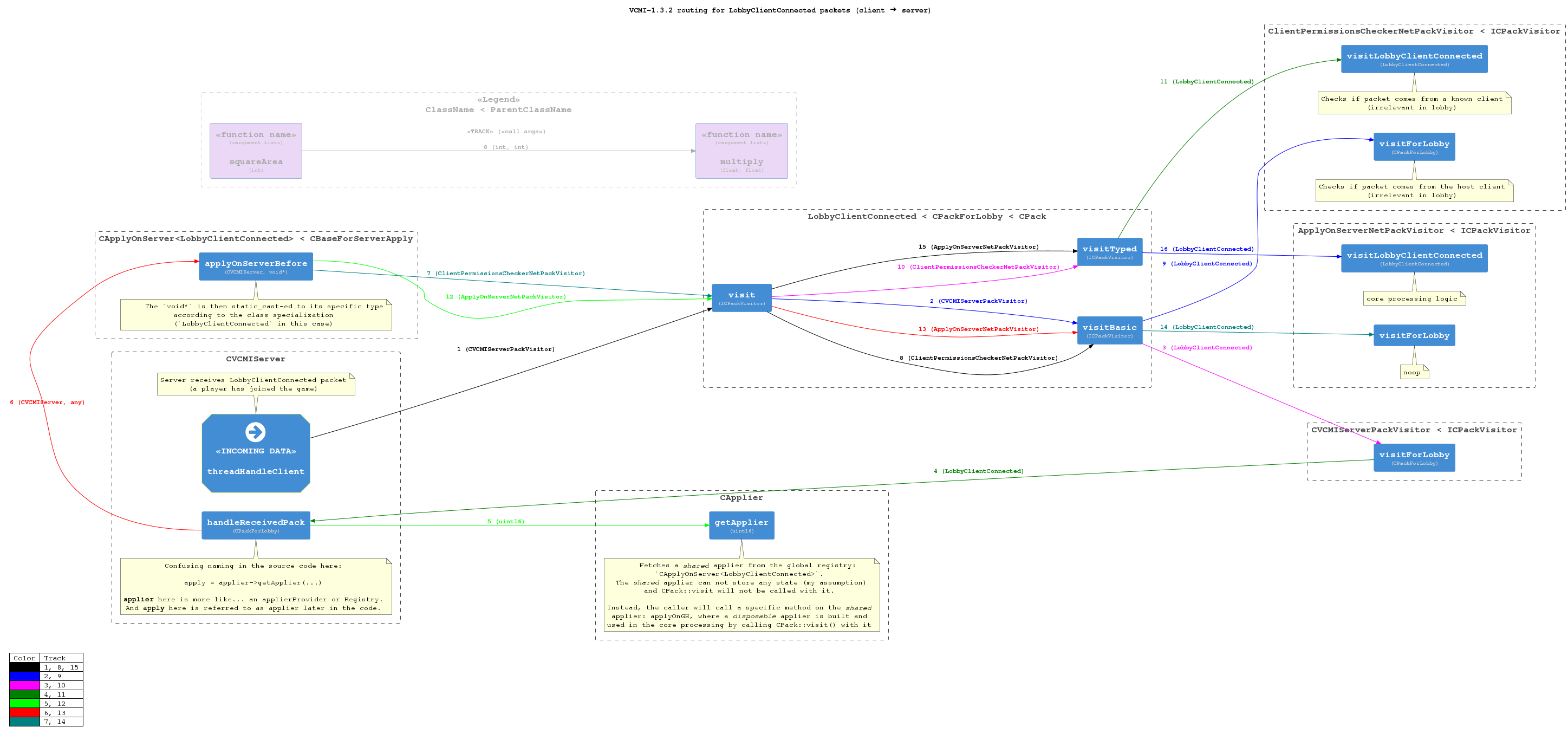

Note: the term “Lobby” in the diagrams refers to the game’s Main Menu (in this case - “New Game” screen) and should not be confused with VCMI’s lobby component for online multiplayer.

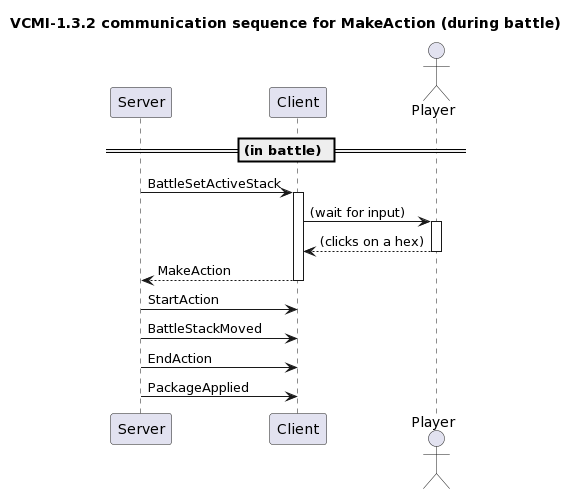

MakeAction, StartAction, etc. are sub-classes of the CPack base class – since C++ is a strongly typed language, there’s a separate class object for each different data structure:

CPack class tree (SVG version here) Whenever I have to deal with a proprietary network communication protocol which I am not familiar with, I tend to examine the raw data sent over the wire to make sure I am not missing anything. So I sniffed a couple of TCP packets using Wireshark and here’s what the raw data looks like:

== MakeAction command packet. Format:

==

== [32-bit hex dump] // [value in debugger] // [dtype] // [field desc]

01 // \x01 ui8 hlp (true, i.e. not null)

FA 00 // 250 ui16 tid (typeid)

00 // \0 ui8 playerColor

29 00 00 00 // 41 si32 requestID

00 // 0 ui8 side

00 00 00 00 // 0 ui32 stackNumber

02 00 00 00 // 2 si32 actionType

FF FF FF FF // -1 si32 actionSubtype

01 00 00 00 // 1 si32 length of (unitValue, hexValue) tuples

18 FC FF FF // -1000 si32 unitValue (INVALID_UNIT_ID)

45 00 // 69 si16 hexValue.hex

The observed hex dump aligns with (parts) of the object information displayed in the debugger, as well the class declarations for MakeAction, its member variable of type BattleAction field and its parent CPackForServer. The communication protocol between the server and the clients is now clear.

However, the data itself does not tell much about the system’s behaviour. There’s a lot going on after that data is received – let’s see what.

Data processing

Any packet that is accepted by a client or server essentially spins a bunch of gears which ultimately change the global game state and, optionally, result in other data packets being sent in response.

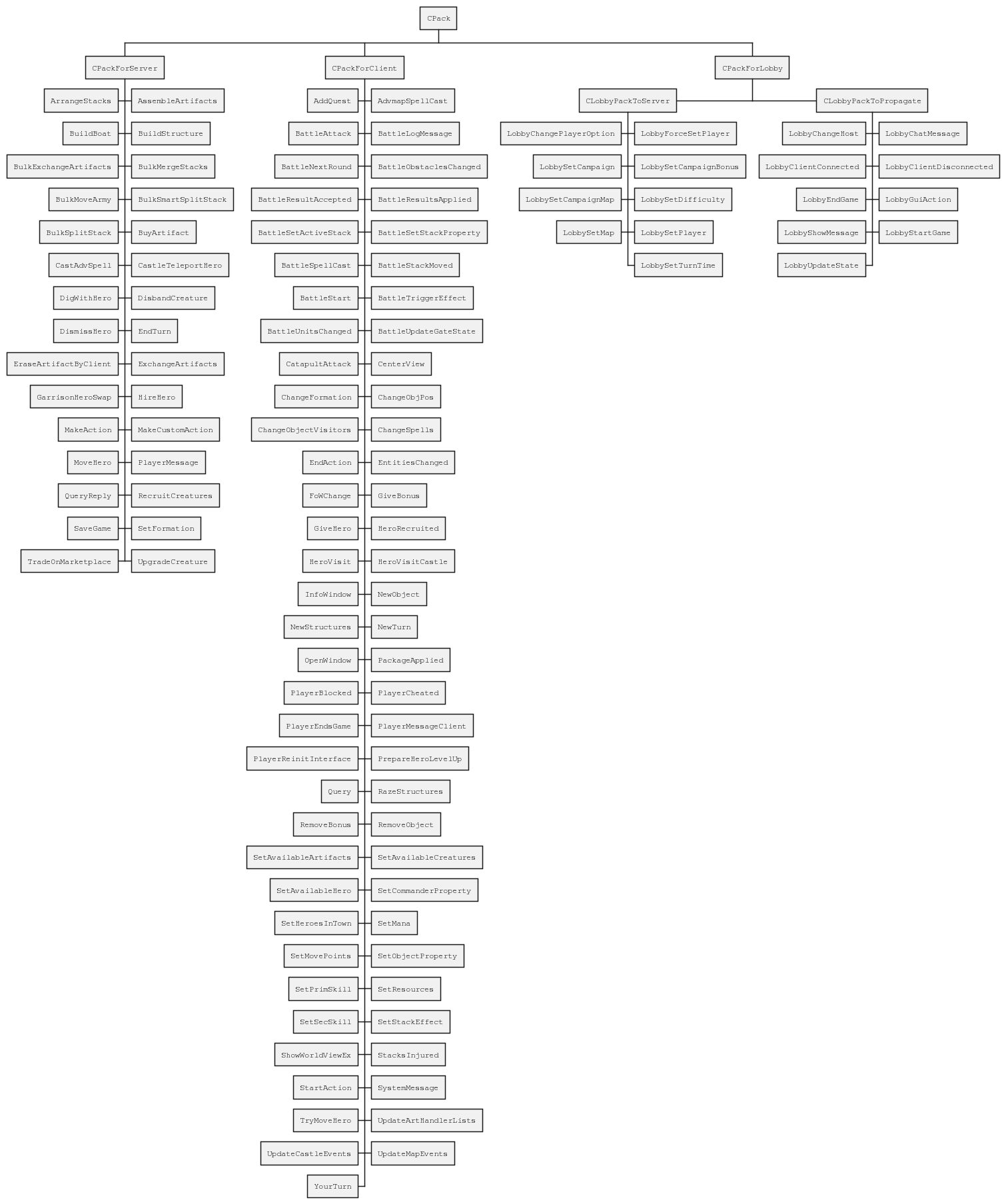

Figuring out the details by navigating through the VCMI codebase is nearly impossible with the naked eye – there are ~300K lines of code in there. That’s where the debugger really comes in handy – with it, I followed the code path of the received data from start to end and mapped out the important processing components involved. Digging deeper into the example above, I visualized the handling of a LobbyClientConnected packet from two different perspectives in an attempt to get a grip on what’s going on:

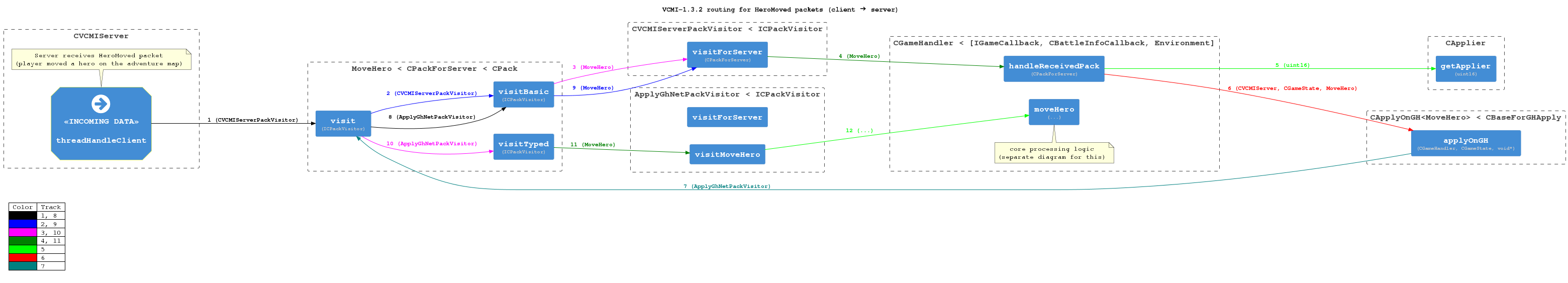

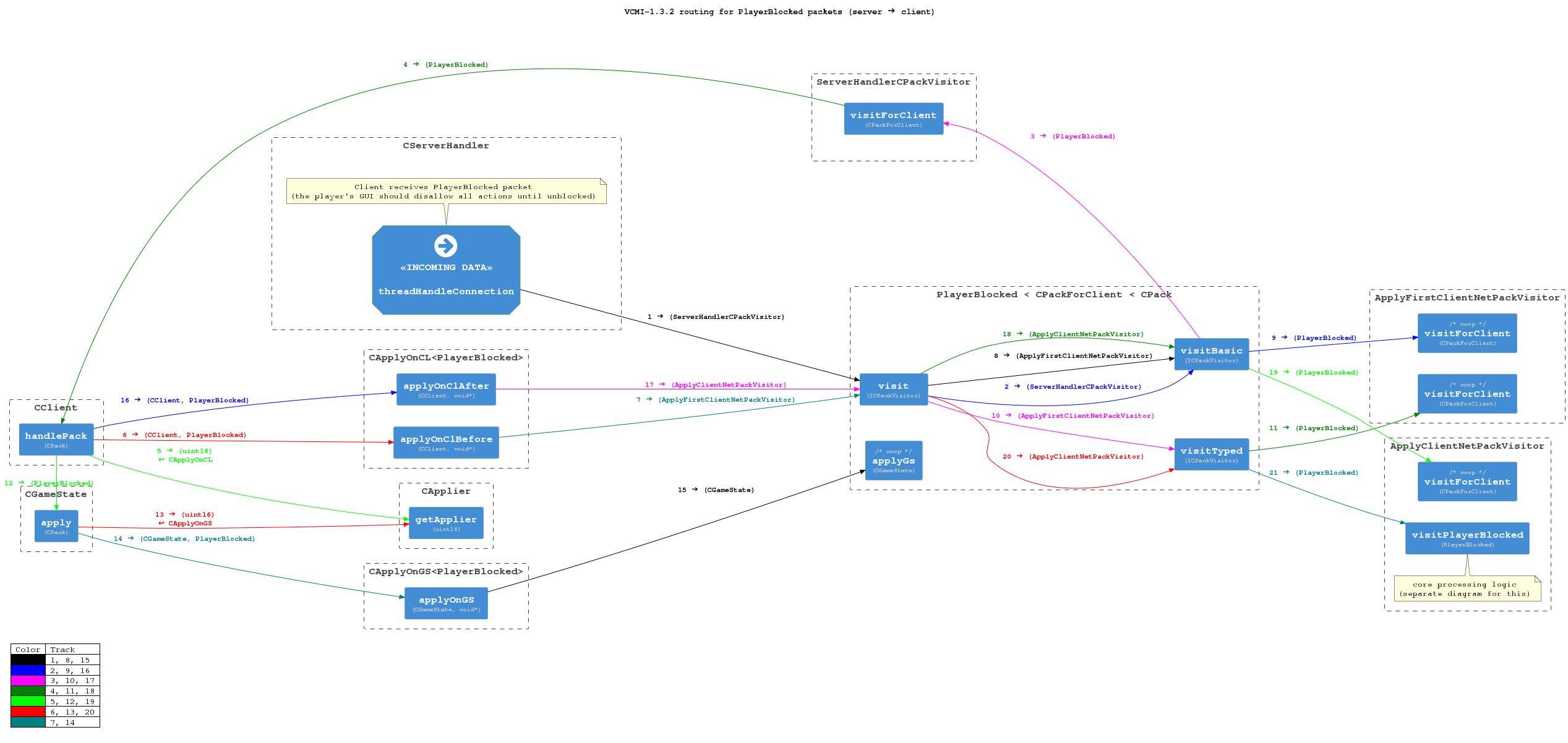

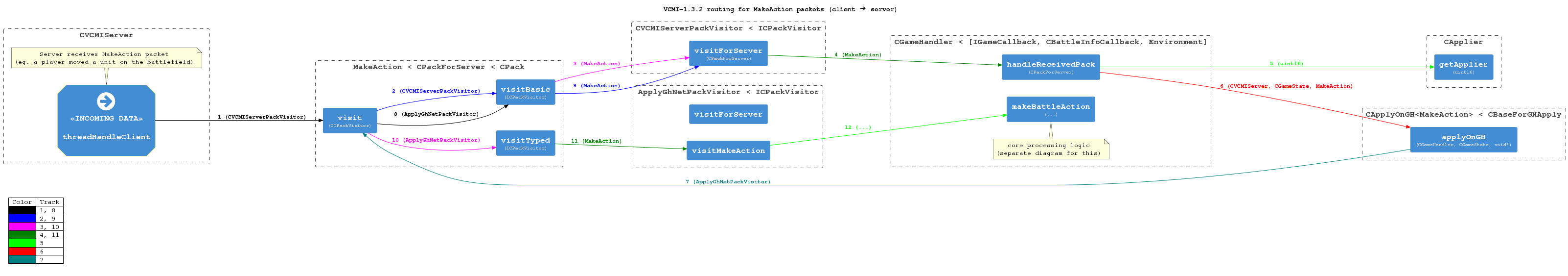

That’s the “short” version, anyway – many irrelevant details and function calls are omitted from the diagrams to keep it readable. But it’s just one of many possible codepaths, considering the number of different packets (see the CPack class tree above). It would be impossible to map them all, but I did map few more as I kept exploring the codebase – I am sharing them here as they might come in handy in the future:

Patterns of the processing logic began to emerge at that point, meaning I had reached a satisfactory level of general understanding about how VCMI works. It was time to think about transforming it into a reinforcement learning environment.

Optimizing VCMI for RL

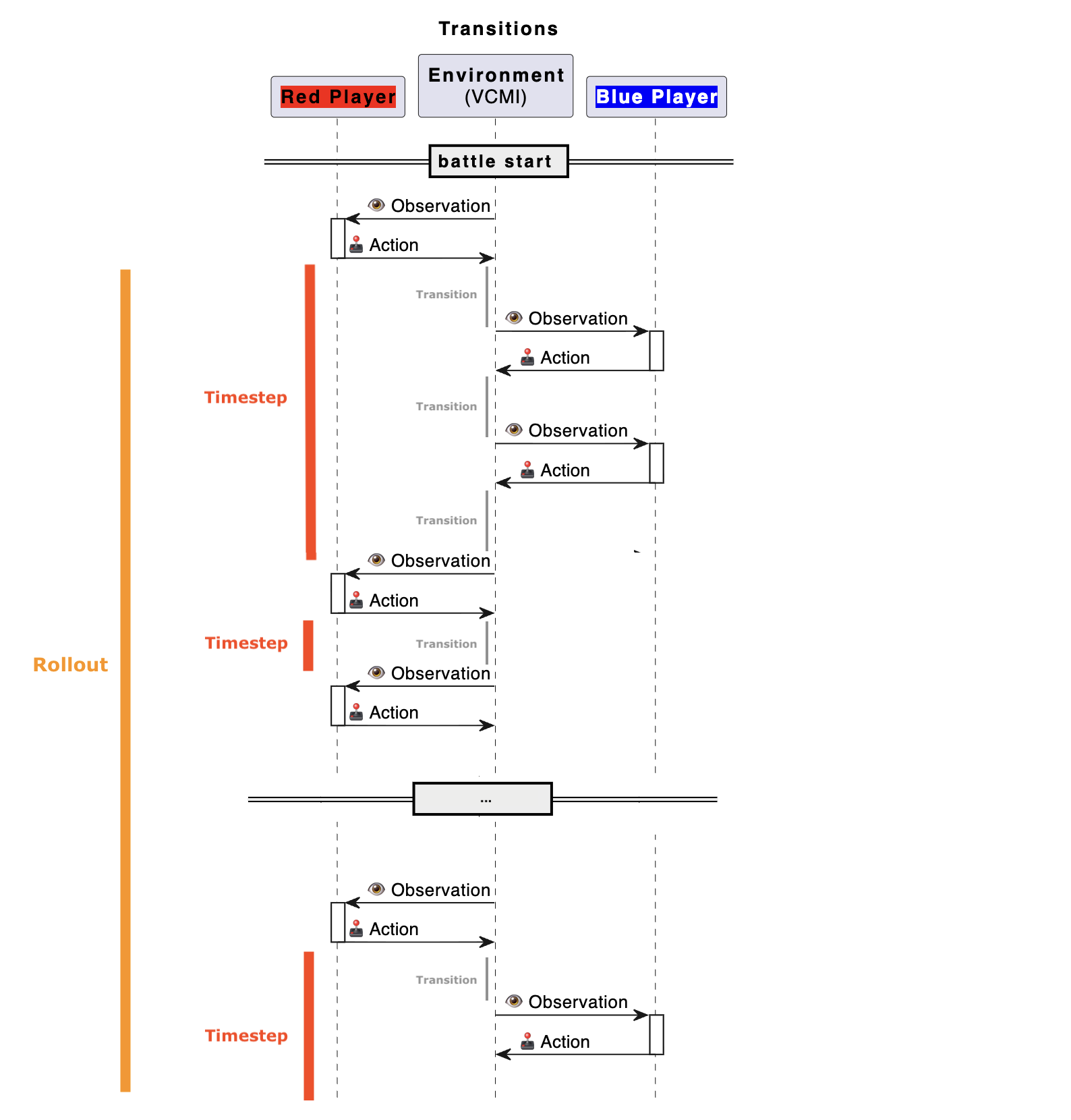

VCMI’s user-oriented design makes it unsuitable for training AI models efficiently. On-policy RL algorithms like PPO are designed to operate in environments where state observations can collected at high speeds and training a battle AI is a process that will involve a lot of battles being played. We are talking millions here.

Quick battles

With the animation speed set to max and auto-combat enabled, a typical 10 round battle takes around a minute. Ain’t nobody got time for that.

The game features a “quick combat” setting which causes battles to be carried out in the background without any user interaction (the user’s troops are controlled by the computer instead). With quick combat enabled, a battle gets resolved in under a second, which is a great improvement. Clearly, combat training should be conducted in the form of quick combats.

But what good is a sub-second combat if it takes 10+ seconds to restart?

Quick restarts

Fortunately, VCMI features the potentially helpful “quick combat replays” setting. Sadly, it allows only a single manual replay per battle and only when the enemy is a neutral army - not particularly useful in my case. What I need is infinite quick replays.

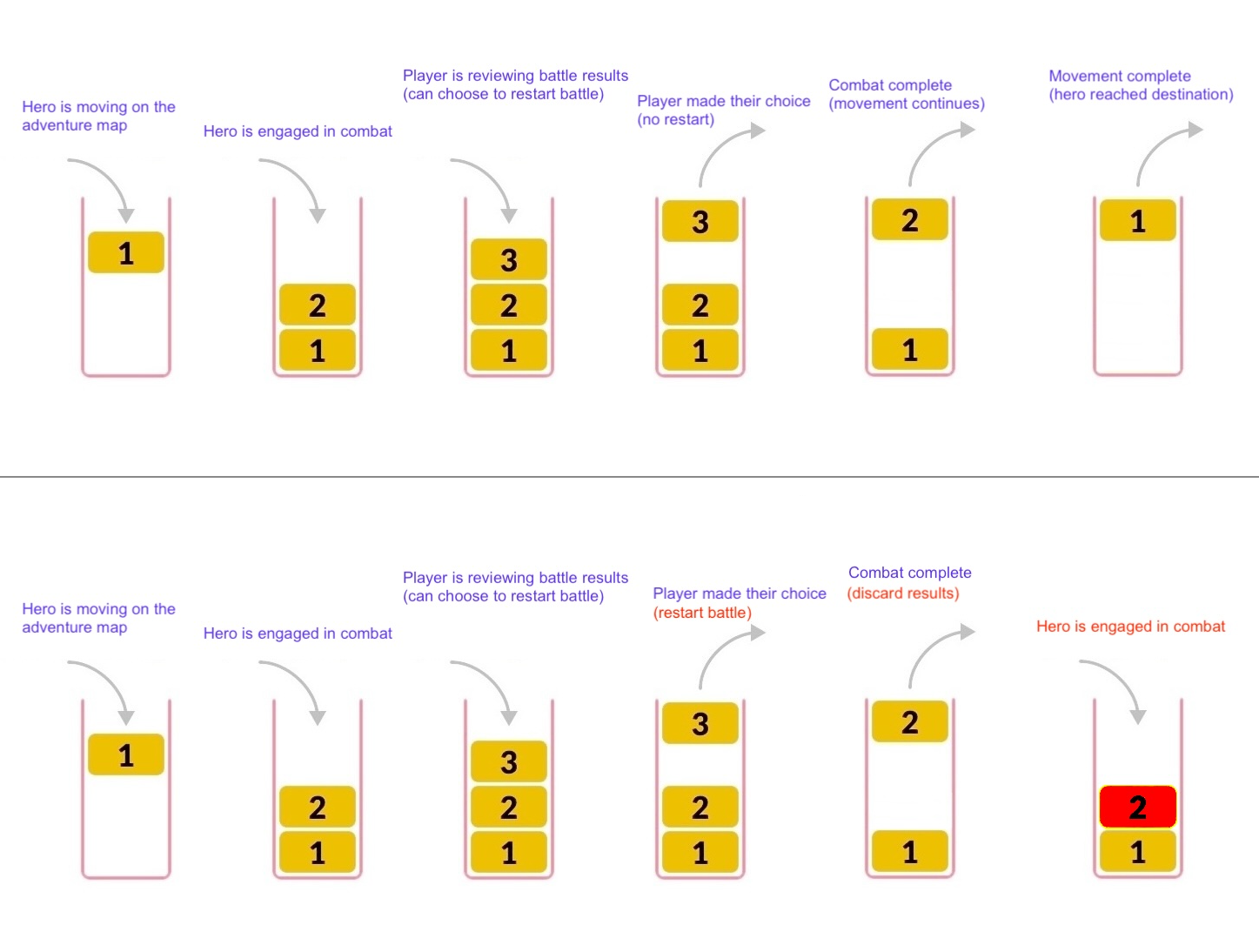

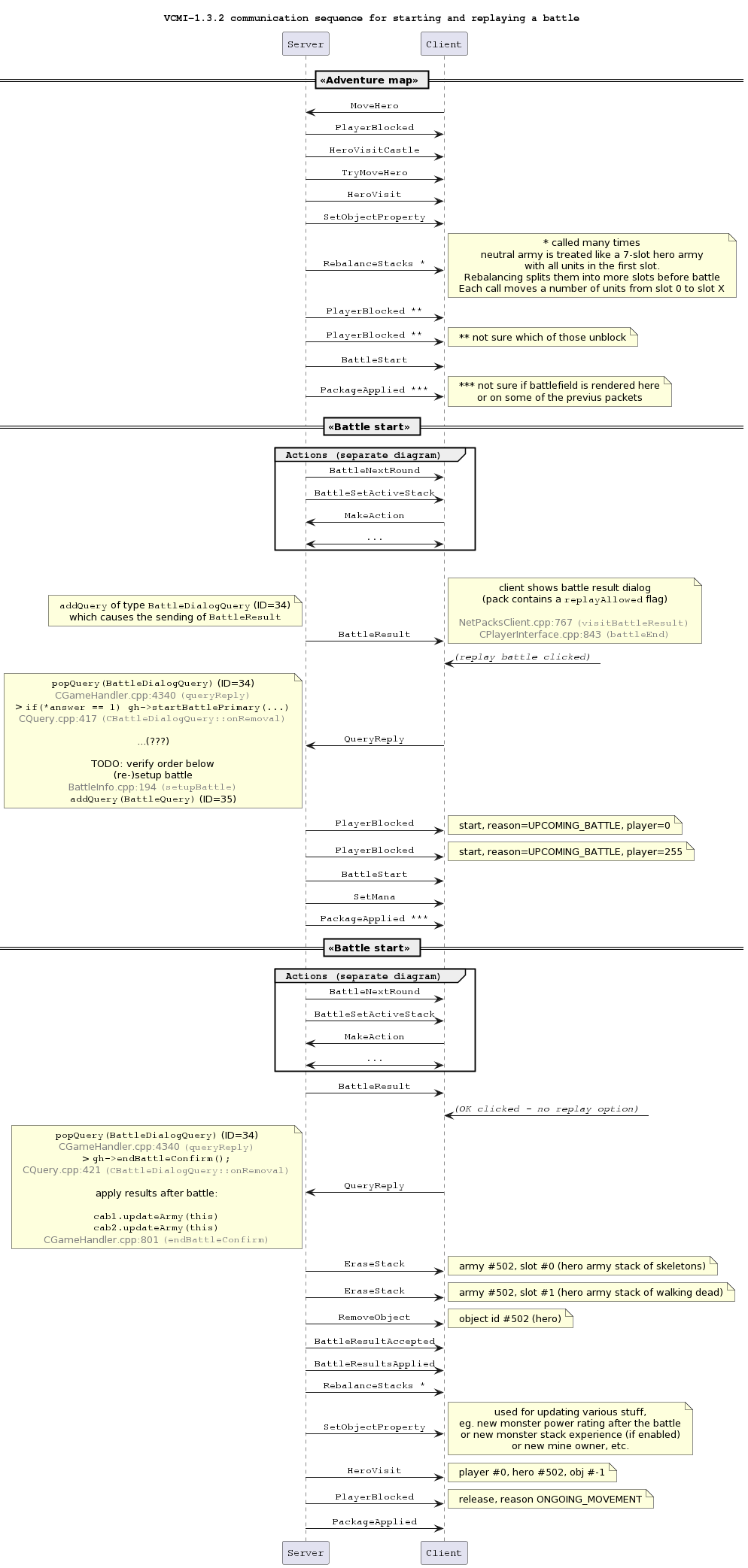

A deeper look into VCMI’s internals reveals the query stack, where each item roughly corresponds to an event whose outcome depends on other events which might occur in the meantime. When the player chooses to restart combat, the results from battle query #2 are not applied and the entire query is re-inserted back in the stack (with a few special flags set).

Removing the restart battle restrictions involved relatively minor code changes and even revealed a small memory leak in VCMI itself (at least for VCMI v1.3.2, it should already be fixed in v1.4+)

Benchmarks

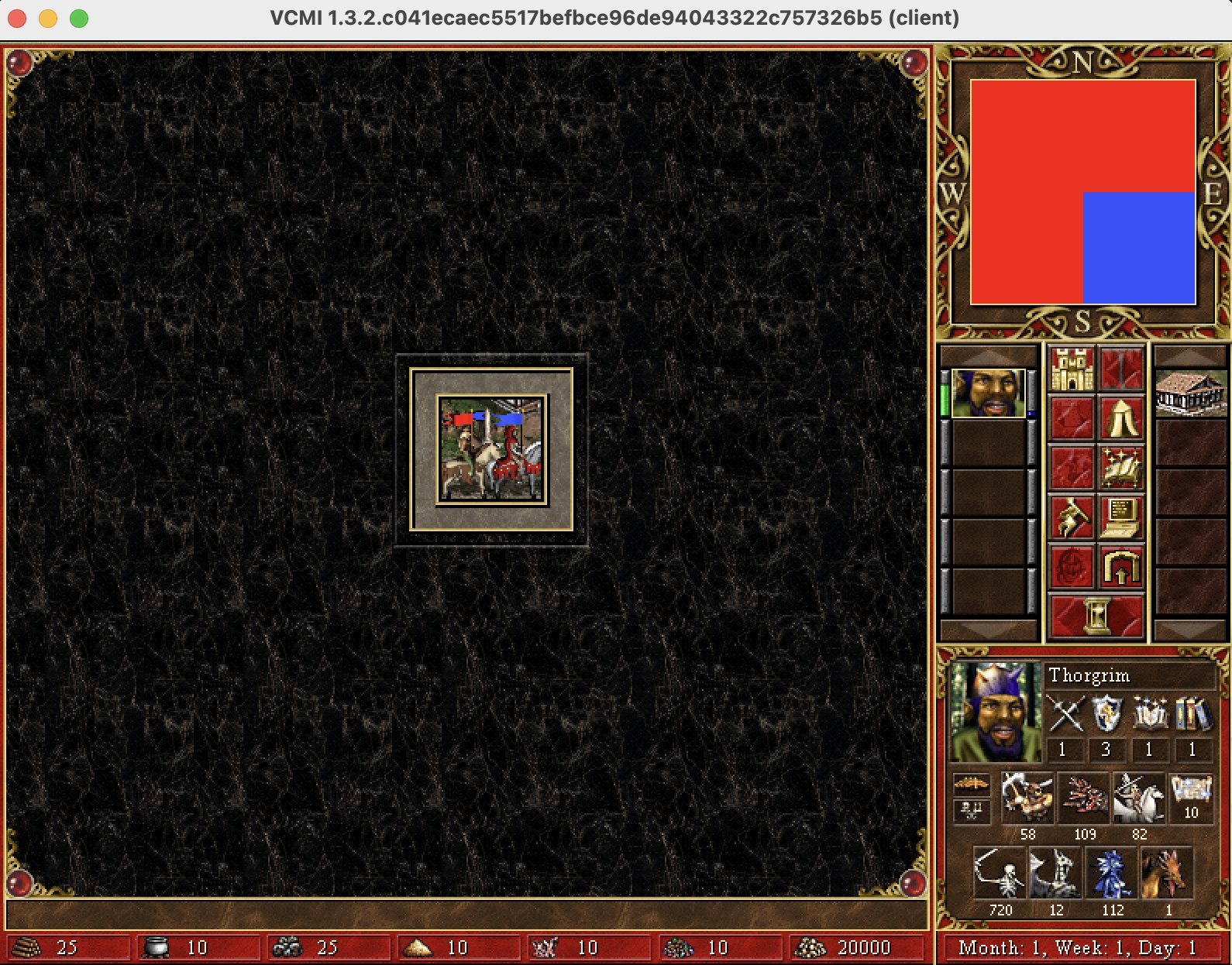

My poor man’s benchmark setup consists of a simple 2-player micro adventure map (2x2) where two opposing armies of similar strength (heroes with 7 groups of units each) engage in a battle which is restarted immediately after it ends:

The benchmark was done on my own laptop (M2 Macbook Pro). Here are the measurements:

- 16.28 battles per per second

- 862 actions per second (431 per side)

The results were good enough for me - there was no need to optimize VCMI further at this point. It was about time I started thinking on how to integrate it with the Python environment.

Embedding VCMI

The Farama Gymnasium (formerly OpenAI Gym) API standard is a Python library that aims to make representing RL problems easier. I like it because of its simplicity and wide adoption rate within the python RL community (RLlib, StableBaselines, CleanRL are a few examples), so I going to use it for my RL environment.

Communicating with a C++ program (i.e. VCMI) from a Python program was a new and exciting challenge for me. Given that the Python interpreter itself is written in C++, it had to be possible. I googled a bit and decided to go with pybind11, which looked like the tool for the job.

I quickly ran into various issues related to memory violations. Anyone that has worked with data pointers (inevitable in C++) has certainly encountered the infamous Undefined Behaviour™ monster that can make a serious mess out of any program. Turns out there is a very strict line one must not cross when embedding C++ in Python: accessing data outside of a python thread without having acquired the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL). A Python developer never really needs to think about it until they step out of Python Wonderland and enter the dark dungeons of a C++ extension. I managed to eventually get the hang of it and successfully integrated both programs. A truly educational experience.

While experimenting with pybind11, I was surprised to find out VCMI can’t really be embedded as it refuses to boot in a non-main thread. Definitely a blocker, since the main thread during training is the RL script, not VCMI. Bummer.

A quick investigation revealed that the SDL loop which renders the graphical user interface (GUI) was responsible for the issue. This GUI had to go.

Removing the GUI

There have always been many reasons to remove the GUI – it is not used during training, consumes additional hardware resources and enforces a limit on the overall game speed due to hard-coded framerate restrictions, so I was more than happy to deal with it now that it became necessary.

The VCMI executable accepts a --headless flag which causes a runtime error as soon as the game is started. Still, the codebase did contain code paths for running in such a mode, so making it work properly should be an easy win. In the end, I decided to introduce a new build target which defines a function which only initializes the SDL (this is required for the game to run) and another function which starts the game but without activating the SDL render loop.

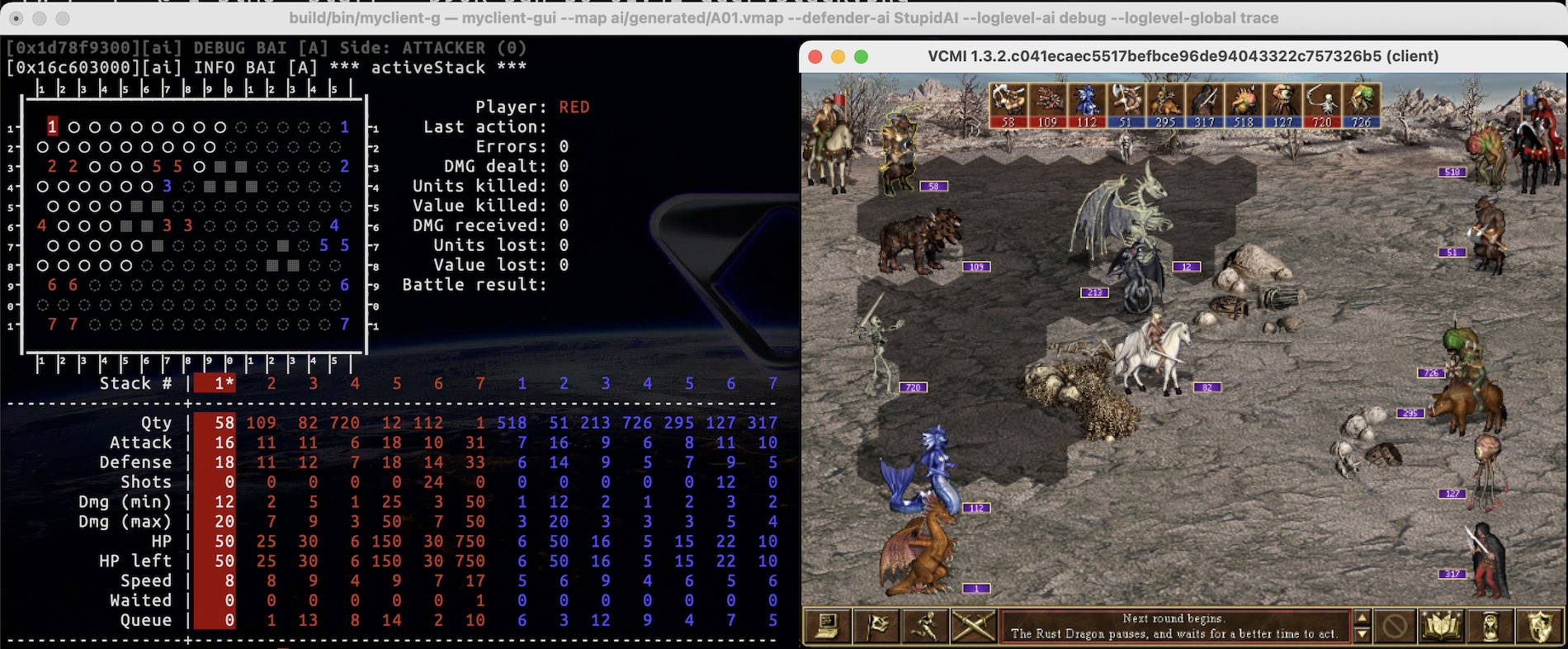

However, with no GUI, it was hard to see what’s going on, so I ended up coding a text-based renderer which is pretty useful for visualizing battlefield state in the terminal:

After pleasing the eye with such a result, it was time to get back to the VCMI-Python integration with pybind11.

Connecting the pieces

I refrained from the quick-and-dirty approach even for PoC purposes as it meant polluting with pybind11 code and dependencies all over the place. A separate component had to be designed for the purpose.

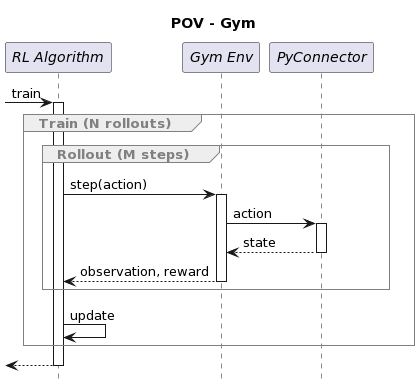

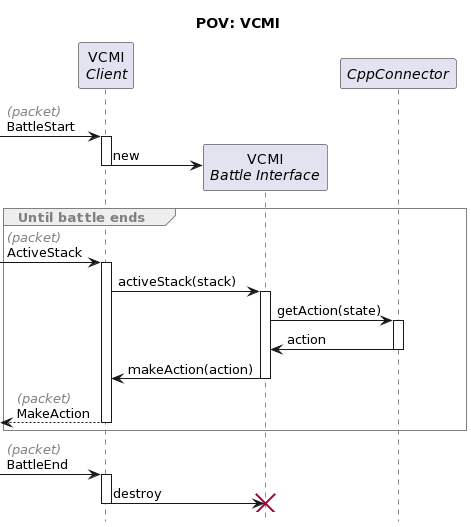

Typically, connecting two components with incompatible interfaces involves an adapter (I call it connector) which provides a clean API to each of the components:

When applying the adapter pattern one must flip their perspective from the local viewpoint of an object in a relationship, to the shared viewpoint of the relationship itself (i.e. both sides of our connector). That’s when one issue becomes apparent: both components are controlled by different entities - i.e. the VCMI client receives input from the VCMI Server, while the gym env receives input from the RL algorithm.

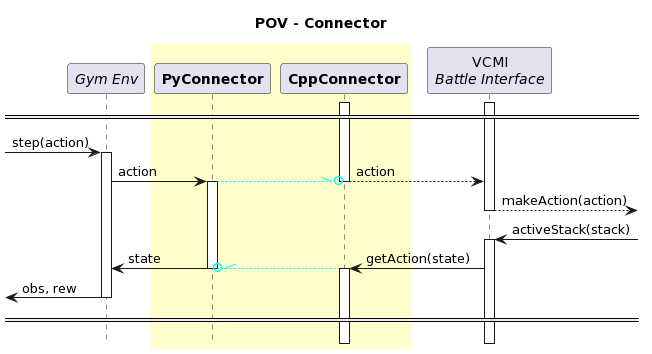

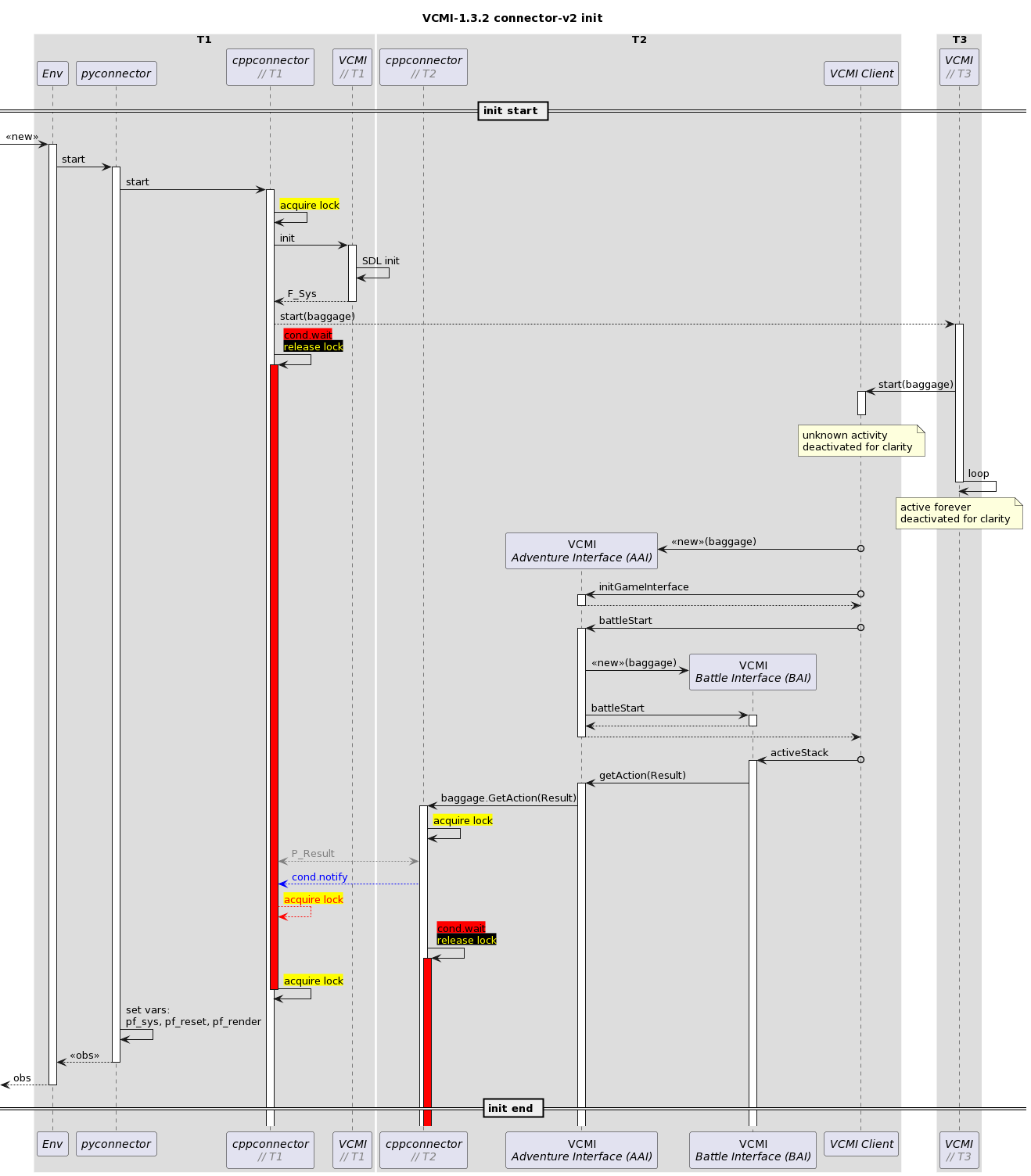

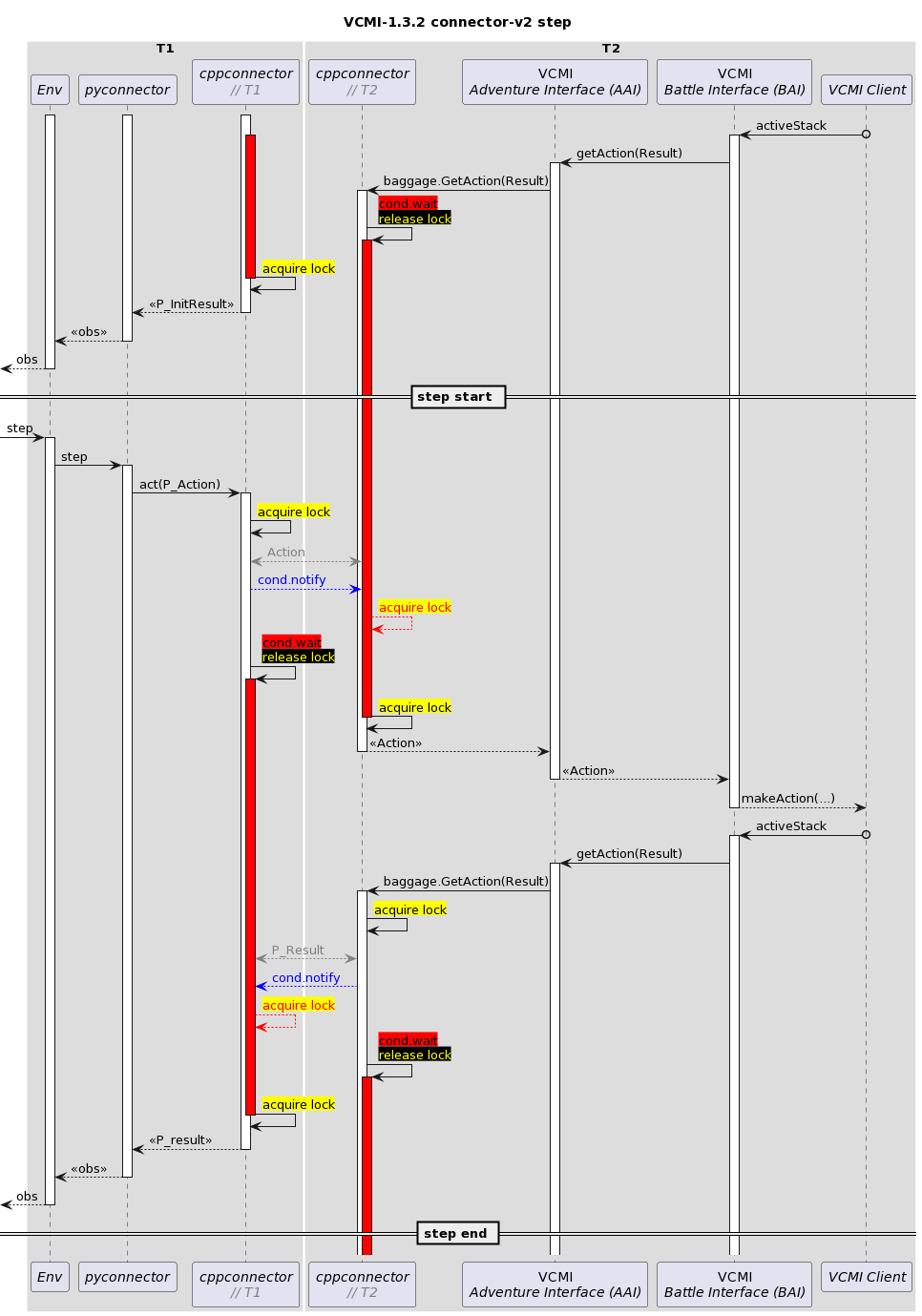

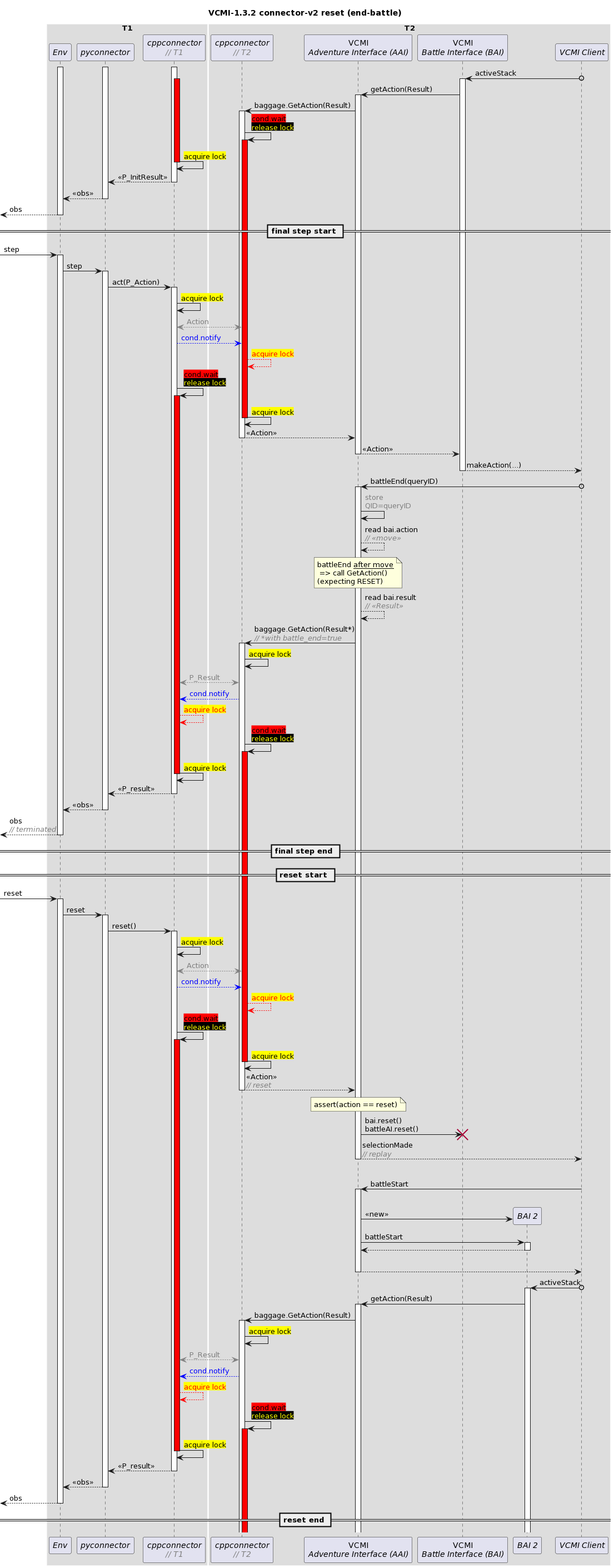

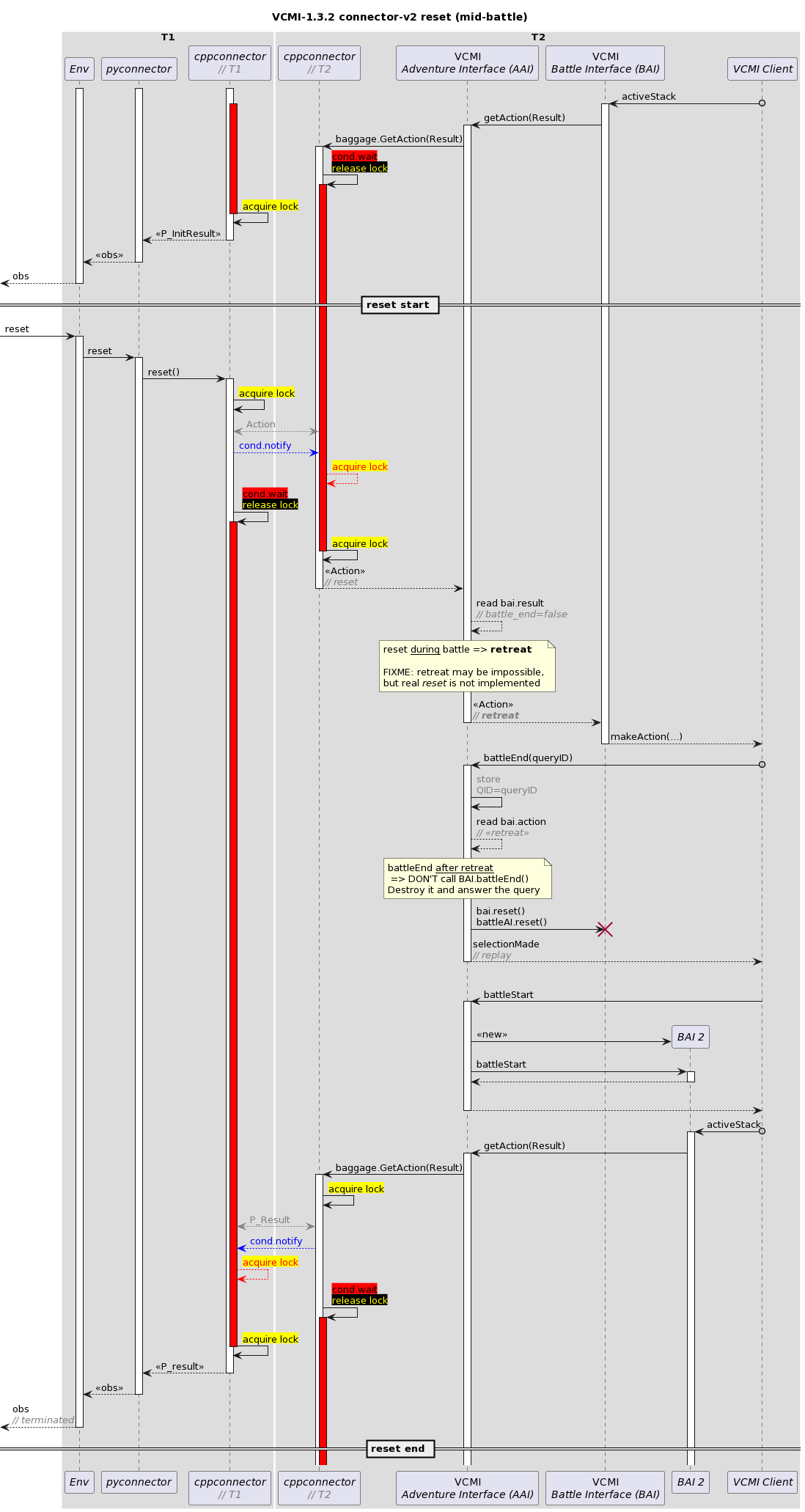

Since both controlling entities (RL script and VCMI server) are otherwise unrelated, the connector is responsible for ensuring that they operate in a mutually synchronous manner. The solution involves usage of synchronization primitives to block the execution of one thread while the other is unblocked:

Some notes regarding the diagrams above:

- The gray background denotes a group of actors operating within the same thread (where

T1,T2, … are the threads). The same actor can operate in multiple threads. - The meaning behind the color-coded labels is as follows:

- acquire lock: a successful attempt to acquire the shared lock. The can be released explicitly via release lock or implicitly at the end of the current call block.

- acquire lock: an unsuccessful attempt to acquire the shared lock, effectively blocking the current thread execution until the lock is released.

- cond.wait: the current thread execution is blocked until another thread notifies it via cond.notify (

condis a conditional variable). - P_Result and Action: shared variables modified by reference (affecting both threads)

- The red bars indicate that the thread execution is blocked.

-

AAIandBAIare the names of my C++ classes which implement VCMI’sCAdventureAIandCBattleGameInterfaceinterfaces. Each VCMI AI (even the default scripted one) defines such classes. -

baggageis a special struct which contains a reference to theGetActionfunction. I introduced the Baggage idiom in VCMI to enable dependency injection - specifically, the Baggage struct is seen as a simplestd::anyobject by upstream code, all the way up untilAAIwhere it’s converted back to a Baggage struct and the function references stored within are extracted. A lot of it feels like black magic and implementing it was a real challenge (function pointers in C++ are really weird). - at the end of a battle, a special flag is returned with the result which indicates that the next action must be

reset - in the middle of a battle, a

resetis still a valid action which is effectively translated to retreat + an a “yes” answer to the “Restart battle” dialog

With that, the important parts of the VCMI-gym integration were now in place. There were many other changes which I won’t discuss here, such as dynamic TCP port allocation, logging improvements, fixes for race conditions when starting multiple VCMIs, building and loading it as a single shared dynamic library, etc. My hands already itched to work on the actual RL part which was just over the corner.

Renforcement Learning

This is the part I found the most difficult. While there are well-known popular RL algos out there, it’s not a simple matter of plug&play (or plug&train :)) It’s a lengthy process involving a cycle of of research, imeplentation, deployment, observation and analysis. It’s why I am always taken aback by my friends’ reactions when telling them about this project:

“The AI algorithms have already been developed, what takes you so long?”

There’s so much I have to say here, but most often, I prefer to avoid talking for another hour about it, so I usually pick an answer as short as “Trust me, it’s not”. And it’s not a good answer, I know that. Call it bad marketing - not just my answer, about this project, but the ubiquitous hype around AI that has made people thinking “That’s it, humanity has found the formula for AI. Now it’s all about having a good hardware”. Well, if that were the case, I wouldn’t bother with this article in the first place. If you are interested in the long answer, read ahead.

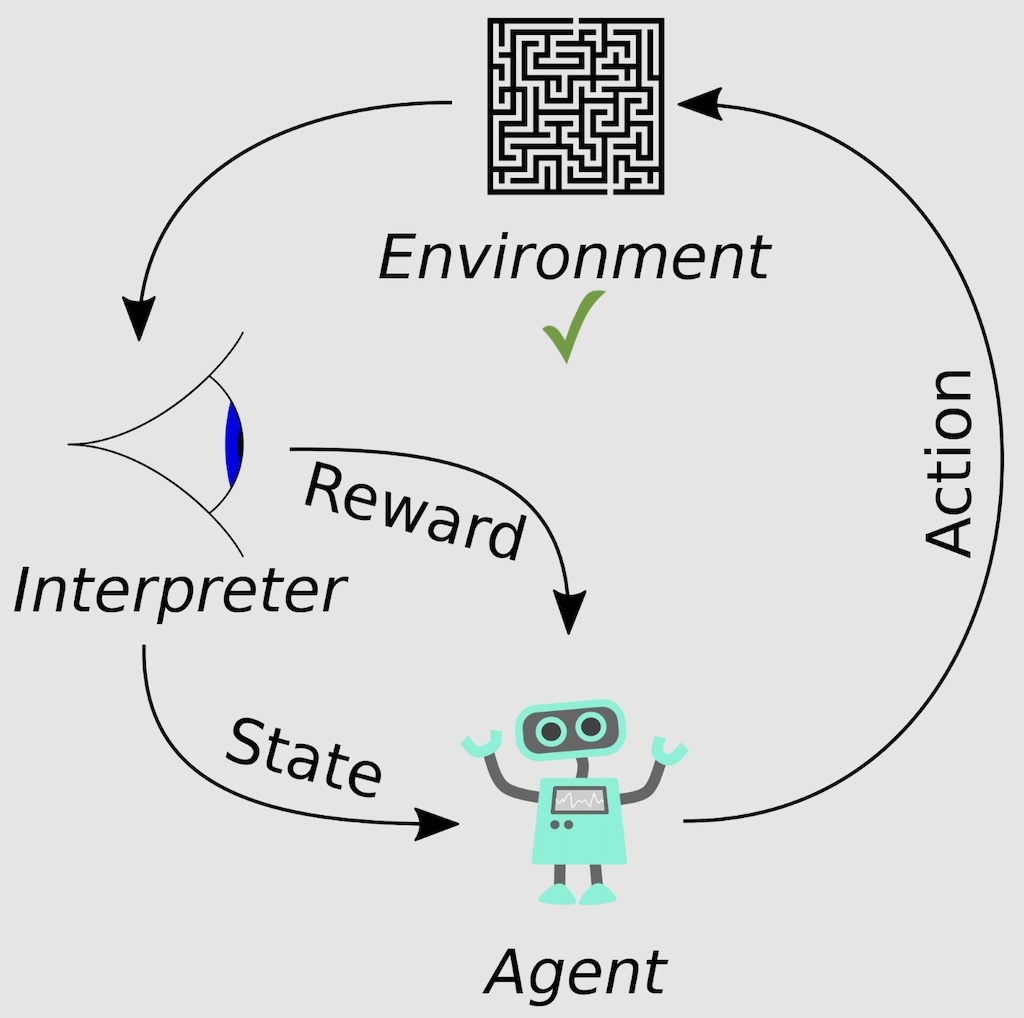

The RL cycle

There’s plenty of information about RL on the web, but I will outline the most essential part it: the action-steate-reward cycle which nicely fits into this simple diagram:

So far I had prepared VCMI as an RL environment, but that’s just one key piece. Next up is presenting its state to the agent.

👁️ Observations

Figuring out which parts of the environment state should be “observable” by the agent (i.e. the observation space) is a balance between providing enough, yet not too much information.

I prefer the Empathic design approch when dealing with such a problem, trying to imagine myself playing the game (and, if possible, actually play it) with very limited information about its current state, taking notes of what’s missing and how important is it. For example, playing a game of Chess without seeing the pieces that have been taken out, or without seeing the enemy’s remaining time is OK, but things get rough if I can’t distinguish the different types of pieces, for example.

Since the agent’s observation space is just a bunch of numbers organized in vectors, it would be nearly impossible for me to interpret it directly – rather, I apply certain post-processing to the observation and transform it into something that my brain can use (yes, that is a sloppy way to describe “user interface”). The important part is this: all information I get to see is simply a projection of the information the agent gets to see.

The observation space went through several design iterations, but I will only focus on the latest one.

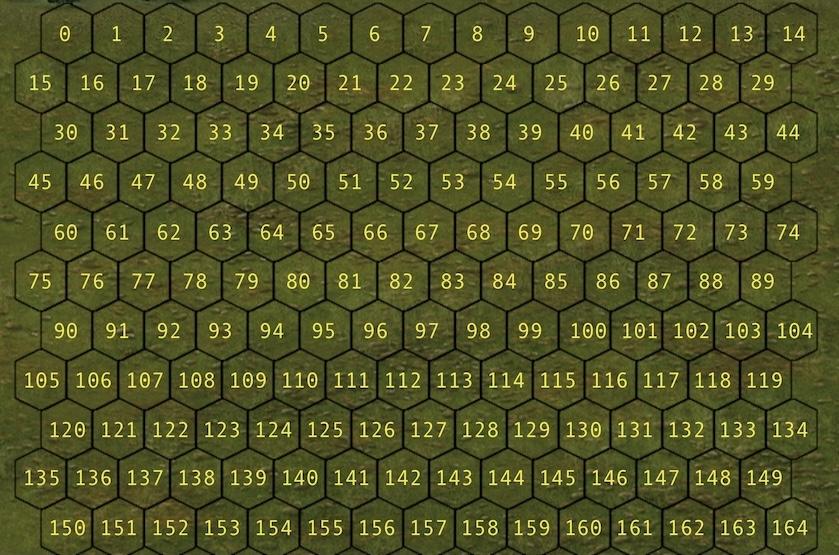

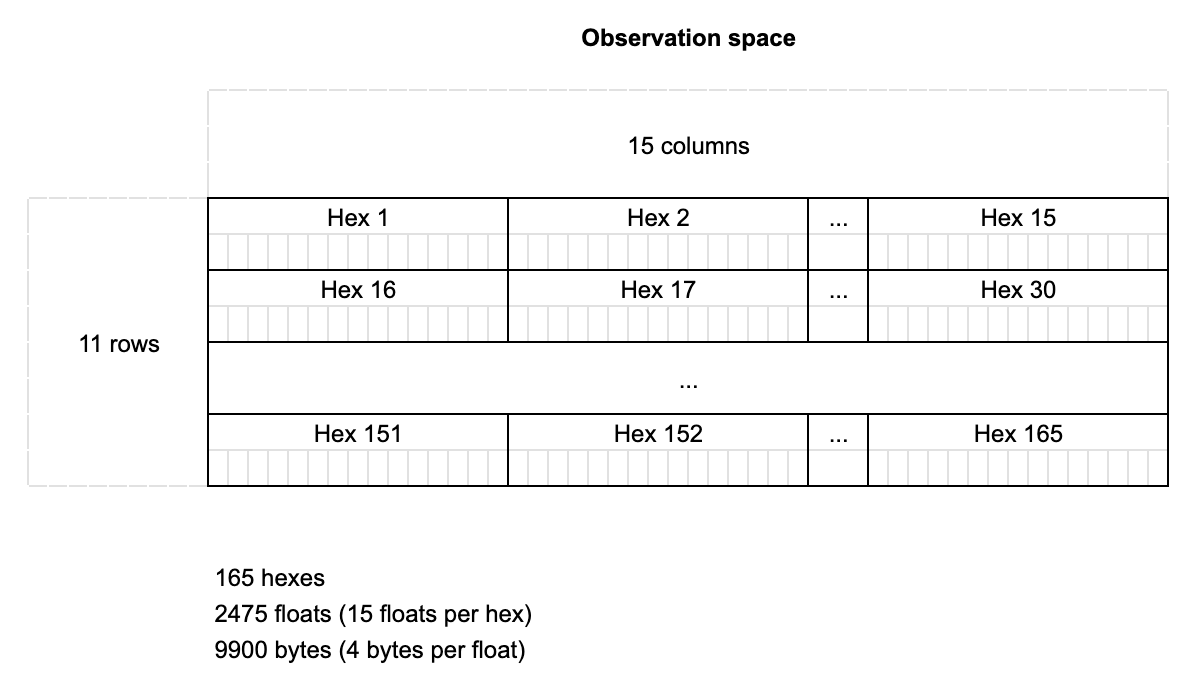

The mandatory component of the observation, the “chess board” equivalent here is the battlefield’s terrain layout. I started out by enumerating all relevant battle hexes that would represent the basis of the observation. The enumeration looks similar to the one used by VCMI’s code, but is different.

Each hex can be in exactly one of four states w.r.t. the currently active unit:

- terrain obstacle

- occupied by a unit

- free (unreachable)

- free (reachable)

This state is represented by a single number. In addition, there are 15 more numbers which represent the occupying creature’s attirbutes, similar to what the player would see when right-clicking on the creature: owner, quantity, creature type, attack, defence, etc.

No information about the terrain’s type (grass, snow, etc.) as well as the creature’s morale, luck, abilities and status effects is provided to the agent. A cardinal sin of RL environment design is to ignore the Markov property, whereby RL algorithms would struggle to optimize the policies, so it was important to not simply hide those attributes, but take them out of the equation:

- terrain is always “cursed ground” (negates morale and luck)

- heroes have no spell books as well as no spellcasting units in their army

- heroes have no passive skills or artifacts affecting the units’ stats

The observation space could be expanded and the restrictions - removed as soon as the agent learns to play well enough.

Note: this is already the case, and additional info was eventually added to the observation: morale, luck, a subset of the creature abilities, total army strength, etc.

🕹️ Actions

Designing the action space is definitely simpler as the agent should be able to perform any action as long as it’s possible under certain conditions. The only meaningful restrictions here are those that prevent quitting, retreating and (as discussed earlier) spell casting.

The total number of possible actions then becomes 2312, which is a sum of:

- 1 “Defend” action

- 1 “Wait” action

- 165 “Move” actions (1 per hex)

- 165 “Ranged attack” actions (1 per hex)

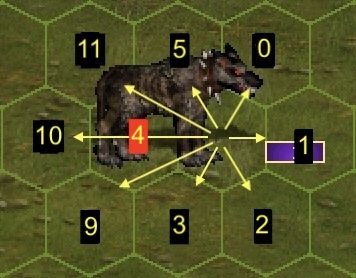

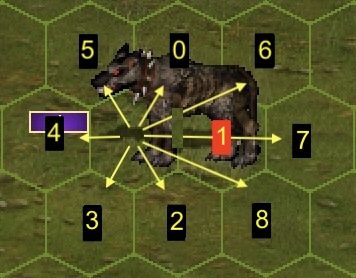

- 165*12=1320 “Melee attack” actions (12 per hex - see image below)

The fact is, most of those actions are only conditionally available at the current timestep. For example, the 1652 actions are reduced to around 600 if the active unit has a speed of 5, as it simply can’t reach most of the hexes. If there are also no enemy units it can target, that number is further reduced to ~200 as the “melee attack” actions become unavailable. If it’s a melee unit, the “ranged attack” actions also become unavailable, reducing the possible actions to around 50 – orders of magnitute lower.

Having such a small fraction of valid actions could hinder the initial stage of the learning process, as the agent will be unlikely to select those actions. Introducing action masking can help with this problem – more on that later.

🍩 Rewards

Arguably the hardest part is deciding when and how much to reward (or punish) agents for their actions. Sparse rewards, i.e. rewards only at the end of the episode, or battle, may lead to (much) slower learning, while too specific rewards (at every step, based on the particular action taken) may induce too much bias, ultimately preventing the agent from developing strategies which the reward designer did not account for.

The reward can be expressed as:

\[R = \sum_{i=1}^nS_i(5D_{i} - V_i\Delta{Q_i})\]where:

- R is the reward

- n is the number of stacks on the battlefield

- Si is

1if the stack is friendly,-1otherwise - Di is the damage dealt by the stack

- Vi is the stack’s AI Value

- ΔQi is the change in the stack’s quantity (number of creatures)

And a (simpler) alternative to the mathematical formulation above:

R = 0

for stack in all_stacks:

points = 5 * stack.dmg_dealt - (stack.ai_value * stack.qty_diff)

sign = stack.is_friendly ? 1 : -1

R += sign * points

The bottom line is: all rewards are zero-sum, i.e. for each reward point given to one side, a corresponding punishment point is given to the other side.

An important note here is that there’s no punishment for invalid actions (or conditionally unavailable actions) – the initial reward design did include such, but it became redundant after I added action masking (see next section).

Note: this reward function became more complex as the project evolved and eventually included damping factors, fixed per-step rewards, scaling based on total starting army value, etc. An essential part of it still corresponds to the above formula, though.

🏋️ Training algorithm

I started off with stable-baselines3’s PPO and DQN implementations, which I have used in the past, and launched a training session where the left-side army is controlled by the agent and the enemy (right-side army) is controlled by the built-in “StupidAI” bot:

The idea was to eventually add more units to each army which would progressively increase the complexity.

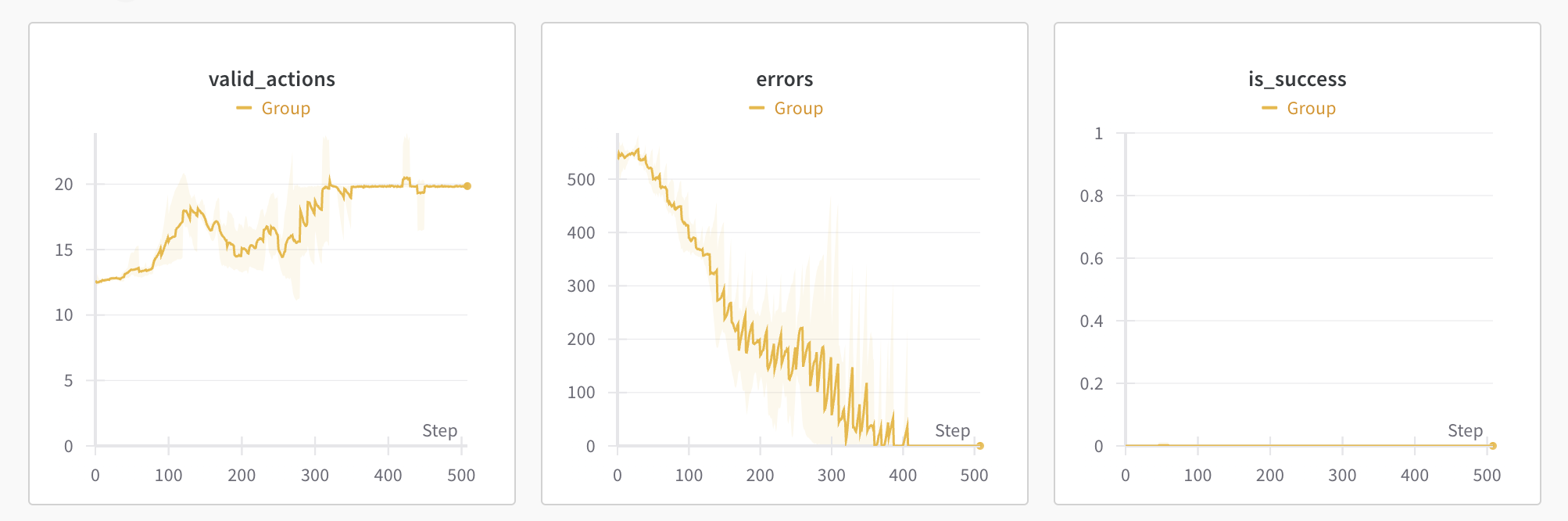

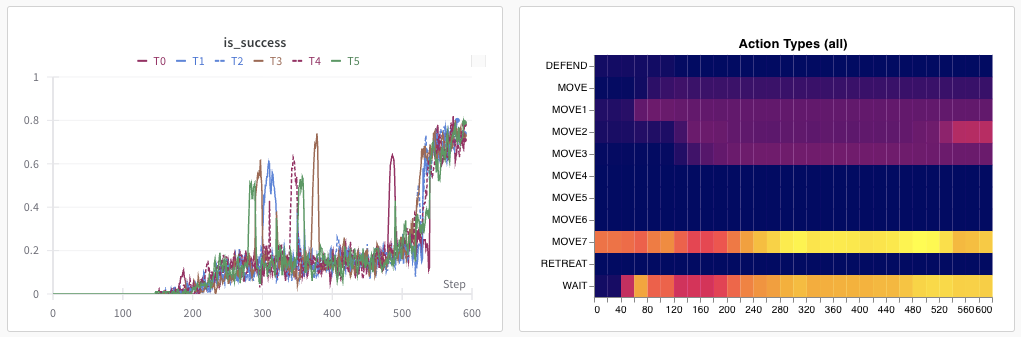

However, one issue quickly popped up: the action space was too big (2000+ actions), while the average number of allowed actions at any given timestep was less than 50. It means an untrained agent has only 2% chance to make an valid action (the initial policy is basically an RNG). The agent was making too many invalid actions and, although it eventually learned to stop making them, it still performed very poorly:

Something was clearly wrong here. Why was the agent unable to win a game? Clearly it was learning: the errors chart shows it eventually stops making invalid actions. I needed more information.

I started reporting aggregated metrics with the actions being taken and visualised them as a heatmap (had to write a custom vega chart in W&B for that). The problem was revealed immediately: the agent’s policy was converging to a single action:

Apparently, all the agent “learned” was that any action except the “Defend” action results in a negative reward (recall that 98% of the actions are invalid at any given timestep). While it does yield a higher reward, it is still a poor strategy that will always lead to a loss. This is referred to as local minima and such a state is usually nearly impossible to recover from.

One option was to try and tweak the negative feedback for invalid actions. Making it too small or completely removing it caused another local minima: convergence into a policy where only invalid actions were taken, as the episode never finished and thus - the enemy could never inflict any damage (the enemy is not given a turn until the agent finishes its own turn by making a valid move). Maybe I should introduce a negative feedback on “Defend” actions…? That would introduce too much bias (defending is not an inherently bad action, but the agent would perceive it as such).

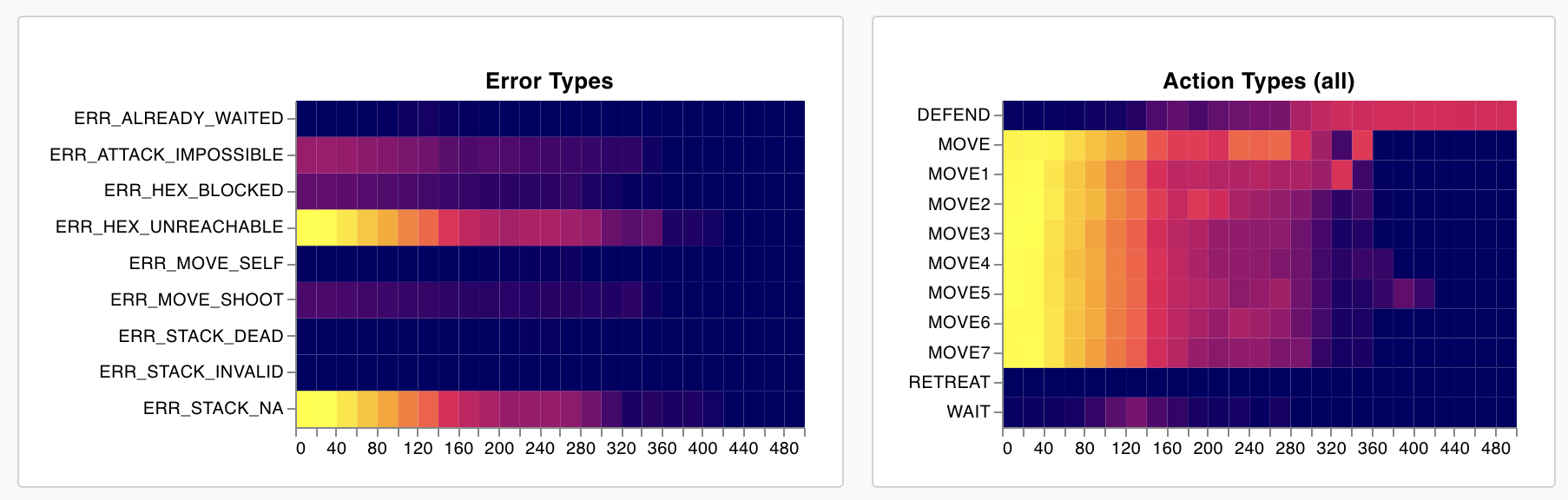

Reshaping the reward signal was not productive here. I had to prevent such actions from being taken in the first place. To do this, I needed to understand how agents choose their actions:

- The output layer of a neural network produces a group of

nvalues (called logits):[s₁, s₂, ..., sₙ], wherenis the number of actions. The logits have no predefined range, i.e.sᵢ ∈ (-∞, ∞). - A

softmaxopration forms a discrete probability distributionP, i.e. the values are transformed into[p₁, p₂, ..., pₙ]wherepᵢ ∈ [0, 1]andsum(p₁, p₂, ..., pₙ) = 1. - Depending on the policy, either of the following comes next:

- Greedy policy: an

argmax(p₁, p₂, ..., pₙ)operation (denoted asmax(pᵢ)in the figure above) returns the indexiof the valuepᵢ = max(p₁, p₂, ..., pₙ), i.e. the action with the highest probability. - Stochastic policy: a

sample(p₁, p₂, ..., pₙ)operation (not shown in the figure above) returns the indexiof a sampled valuepᵢ ~ P.

- Greedy policy: an

Armed with that knowledge, it’s clear that if the output logits are infinitely small, the probability of their corresponding actions will be 0. This is called action masking and is exactly what I needed.

Action masking in PPO was already supported in stable-baselines3’s contrib package, but was not readily available for any other algorithm. If I wanted such a feature for, say, QRDQN, I was to implement it myself. This turned out to be quite difficult in stable-baselines3, so I decided to search for other RL algorithm implementations which would be more easily extensible. That’s how I found cleanrl.

CleanRL is a true gem when it comes to python implementations of RL algorithms: the the code is simple, concise, self-contained, easy to use and customize, excellent for both practical and educational purposes. It made it easy for me to add action masking to PPO and QRDQN (an RL algorithm which I implemented on top of cleanrl’s DQN). Prepending an “M” to those algos was my way of marking them as augmented with action masking (MPPO, MQRDQN, etc).

A detailed analysis of the effects of action masking can be found in this paper. I would also recommend this article, which provides a nice explanation and practical Python examples whih helped me along the way.

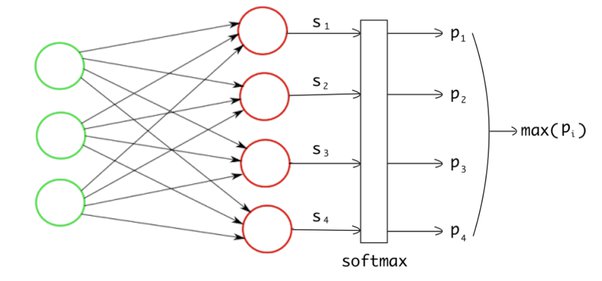

Here’s how the action distribution looked like after action masking was implemented:

The agent was no longer getting stuck in a single-action policy and was instead making meaningful actions: shoot (labelled MOVE7 above) and other attack actions, since all of them were now valid. The agent was now able to decisively win this battle (80% winrate).

🎛️ Hyperparameter optimization

The above results were all achieved with MPPO, however this wasn’t as simple as it may look. The algorithm has around 10 configurable parameters (called hyperparameters), all of which needed adjustments until the desired result was achieved.

Trying to find an optimal combination of hyperparameters is not an easy task. Some of those greatly influence the training process - turning the knob by a hair can result in a completely different outcome. All RL algos have those. While I’ve read that one can develop a pretty good intuition over the years, there’s certainly no way to be certain which combination of values works best for the task – there’s no silver bullet here. It’s a trial-and-error process.

W&B sweeps are one way to do hyperparameter tuning and I’ve successfully used them in previous RL projects. The early stopping criteria helps save computational power that would be otherwise wasted in poorly performing runs, but newly started runs need to learn everything from scratch. There had to be a better way.

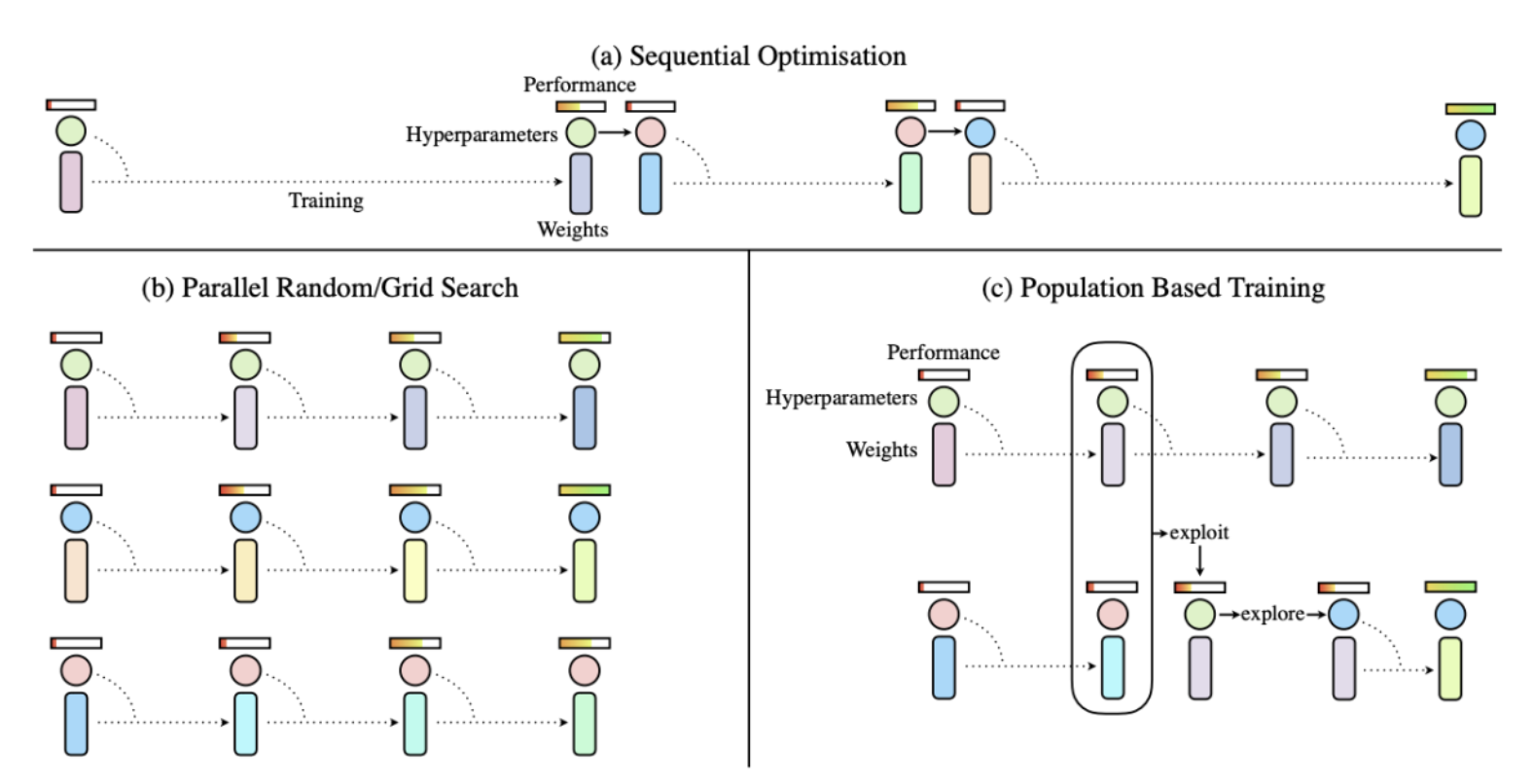

That’s how I learned about the Population Based Training (PBT) method. It’s essentially a hyperparameter tuning technique that does not periodically throw away your agent’s progress. While educating myself on the topic, I stumbled upon the Population Based Bandits (PB2) method, which improves upon PBT by leveraging a probabilistic model for selecting the hyperparameter values, so I went for it instead.

At regular intervals, PBT (and PB2) will terminate lifelines of poorly performing agents and spawn clones of top-performing ones in their stead.

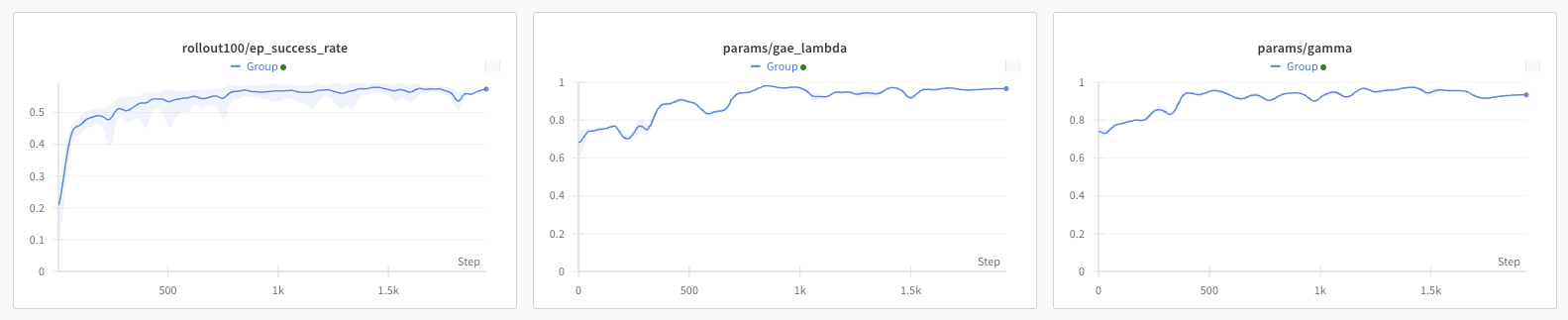

PB2 certainly helped, but this seems mostly a result of its “natural selection” feature, rather than hyperparameter tuning. In the end, a single policy was propagated to all agents and the RL problem was solved, but huge ranges of hyperparameters remained unexplored. Apart from that, PB2’s bayesian optimization took took 20% of the entire training iteration time (where 1 iteration was ~5 minutes), so I opted for the vanilla PBT instead. I have used in all vcmi-gym experiments since and basically all results published here are achieved with PBT.

I must point out that the hyperparameter combination is not static throughought the RL training. It changes. For example, in the early stages of training, lower values for gamma and gae_lambda (PPO params) result in faster learning, since the agent considers near-future rewards as more important than far-future rewards. It makes perfect sense if we compare it to how we (humans) learn: starting with the basics, gradually increasing the complexity and coming up with longer-term strategies as we become more familiar with our task.

📚 Datasets

Achieving an 80% winrate sounds good, but the truth is, the agent was far from intelligent at that point. The obvious problem was that it could only win battles of this (or very similar) type. A different setup (quantities, creature types, stack numbers, etc.) would confuse the agent - the battle would look different compared to everything it was trained for. In other words, the did not generalize well.

This is a typical problem in ML and can usually be resolved by ensuring the data used for training is rich and diverse. In the context of vcmi-gym, the “dataset” can be thought of:

- Army compositions: creature types, number of stacks and stack quantities.

- Battlefield terrains: terrain types, number and location of obstacles.

- Enemy behaviour: actions the enemy takes in a given battle state.

Ensuring as much diversity as possible was a top priority now. The question was how to do it?

My initial attempt was to make use of Gym’s concept for Vector environments, which allows to train on N different environments at once. This means the agent would see N different datasets on each timestep which would provide some degree of data diversity. The problem was that VCMI is designed such that only one instance of the game can run at a time, I had to deal with that first (later submitted it as a standalone contribution).

With vector environments, my agents had access to a more diverse dataset. This, however, lead to (surprise) another problem: the system RAM became a bottleneck, as all those VCMI instances running in parallel needed ~400MB each. At about 30 VCMI instances, my gear (MacBook M2 pro) started to choke, which meant that was the limit of different battle compositions I could use for training. Turned out it’s not enough – the agent was still unable to generalize well. I needed a lot more than 30 armies.

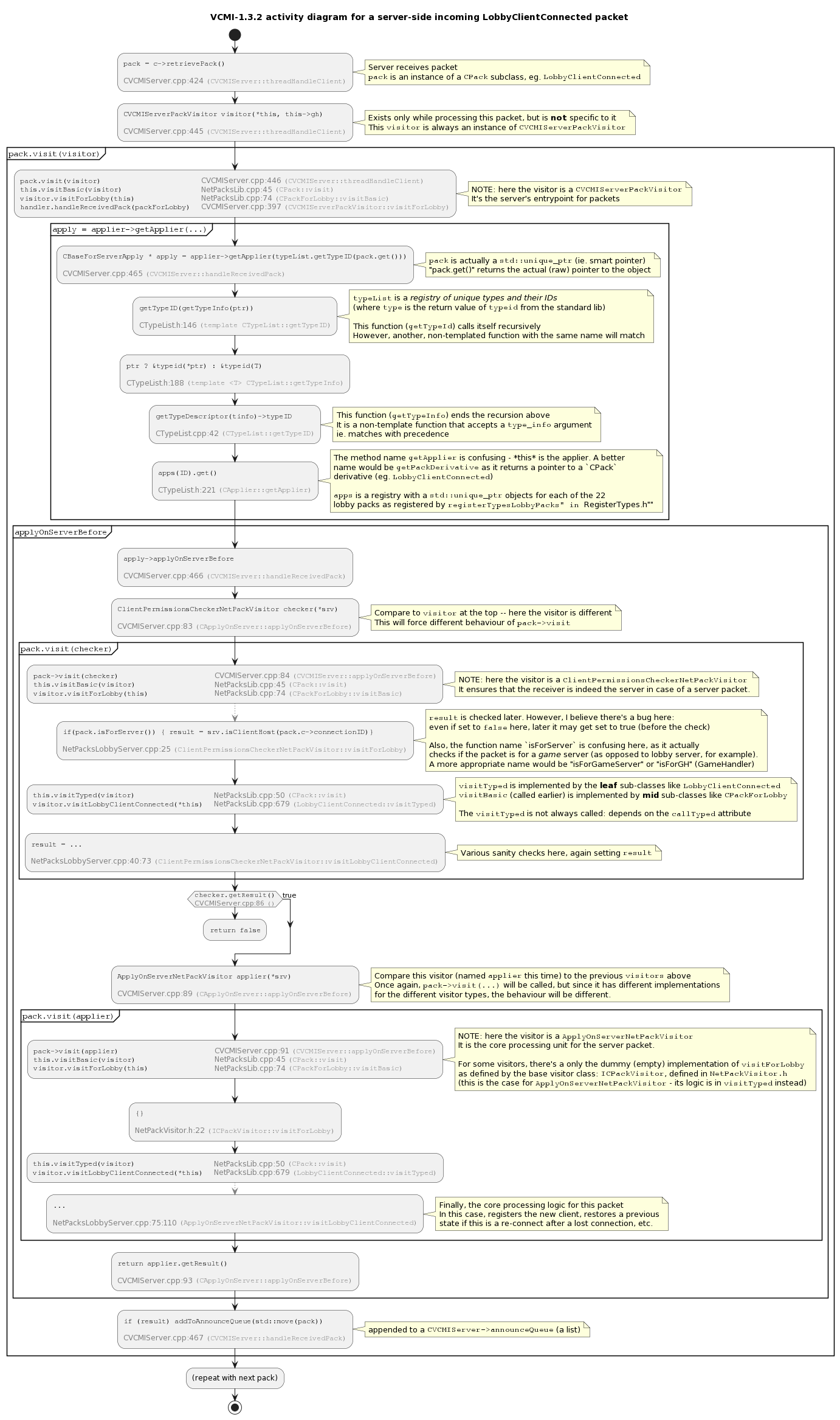

I delved into the VCMI codebase again in search for a way to dynamically change the armies on each restart. Here’s the what the server-client communication looks like when there’s a battle:

The BattleStart server packet is the culprit here. It contains stuff like hero and army IDs, map tile, obstacles, etc. Typically, those don’t change when a battle is re-played, so I plugged in a server-side function which modifies the packet before it gets sent, setting a pseudo-random tile, obstacle layout and army ID. The thing is, the army ID must refer to an army (i.e. hero) object already loaded in memory. In short, the army must already exist on the map, but my test maps contained only two heroes.

Technically, it is possible to generate armies on-the-fly (before each battle), but the problem is: those armies will be imbalanced in terms of strength. This will introduce unwanted noise during training, as agents will often win (or lose) battles not because of their choice of actions, but simply because the armies were vastly different in strength. Poor strategies may get reinforced as they result in a victory which occurred only because the agent’s army had been too strong to begin with. The only way to ensure armies are balanced is to generate, test and rebalance them beforehand, ensuring all armies get equal chances of winning.

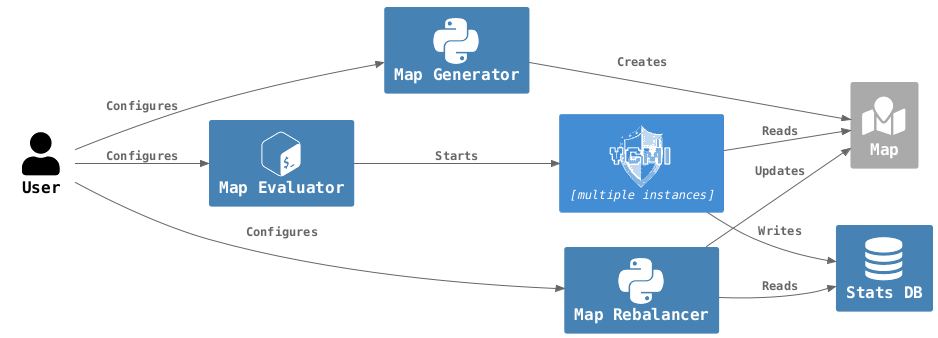

This meant I had to see how VCMI maps are generated, write my own map generator, produce map with lots of different armies and then test and rebalance it until it was ready to be used as a training map. It was quite the effort and ultimately resulted in an entire system comprised of several components:

The cycle goes like this:

- Generate a map with many heroes (i.e. armies) of roughly similar strength

- Evaluate the map by collecting results for each army based on the battles lead by the built-in bot on both sides

- Rebalance the map by adding/removing units from the armies based on aggregated results from 2.

- Repeat step 2. and 3. until no further rebalancing is needed

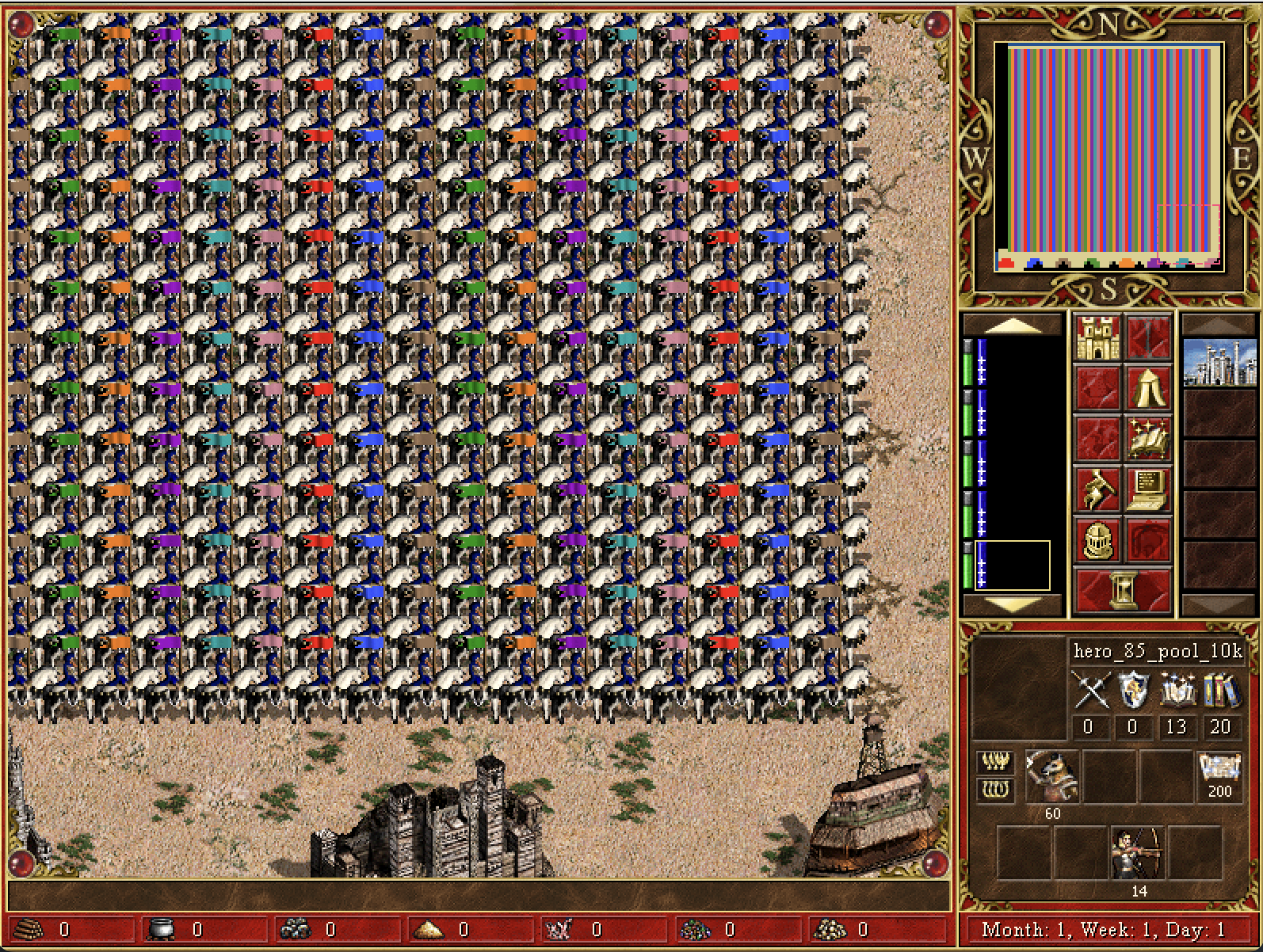

Speaking in numbers, I have been using maps with 4096 heroes, which means there are more than 16M unique parings, making it very unlikely that the agent will ever train with the exact same army compositions twice. There’s a catch here: in HOMM3, there’s no way to have 4096 heroes on the map at the same time (the hero limit is 8). Fortunately, VCMI has no such limit, but imposes another restriction: there can’t be duplicate heroes on the map, and the base game features less than 200 heroes in total. To make this possible, I had to create a VCMI “mod” which adds each of those 4096 heroes as a separate hero type and the issue was gone:

That partly solved the issue with the diverse training data. The only issue with this approach was that all armies were of equal strength - for example, all armies were corresponding to a mid-game army (60-90 in-game days). This meant that the agent had less training experience with early-game (weaker) armies, as well as late-game (stronger) armies. I later improved this map generator and added the option to create pools of heroes, where all heroes within a pool have equal strength, but heroes in different pools have different stregths. Here is how one such map looks like:

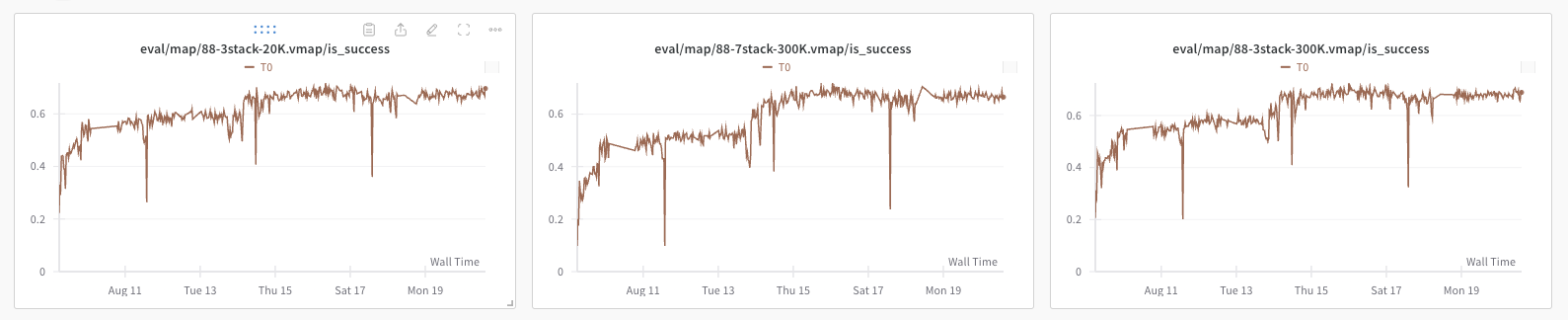

By training on those maps, agents were able to generalize well and maintain steady performance across a wide variety of situations. Below are the results achieved by an agent trained on a 4096-army map and then evaluated on an unseen data set:

The dataset was unseen in the sense that it included armies of total strength 20K and 300K (neither can be found in the training dataset). The battle terrain and obstacles were not exactly unseen, as there is a finite combination of possible terrains and the agent had probably encountered them all before. The enemy behaviour, however, was also new, since all training is done vs. the scripted “StupidAI” bot, while half of the evaluation is done vs. “BattleAI” (VCMI’s strongest scripted bot).

Having said all this, I still haven’t described how exactly I evaluate the those models, so keep reading ahead if you want to know more.

🕵️ Testing (evaluation)

Evaluating the trained agents is a convenient way to determine if the training is productive. A typical problem that occurs during training is overfitting: the metrics collected during training are good, but the metrics collected during testing are not.

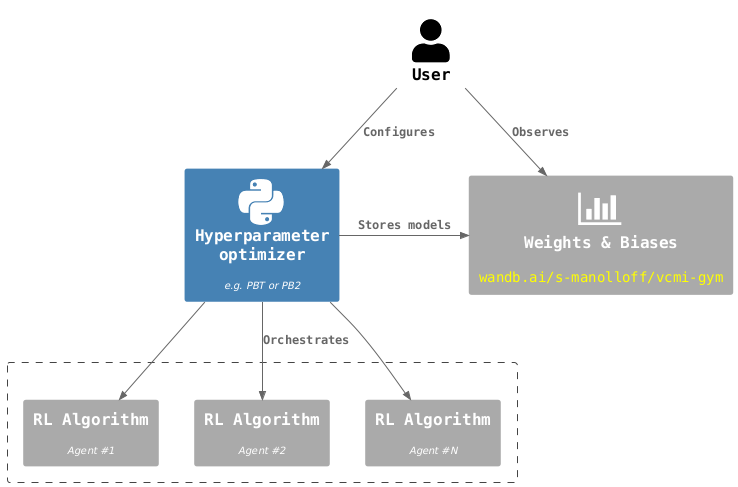

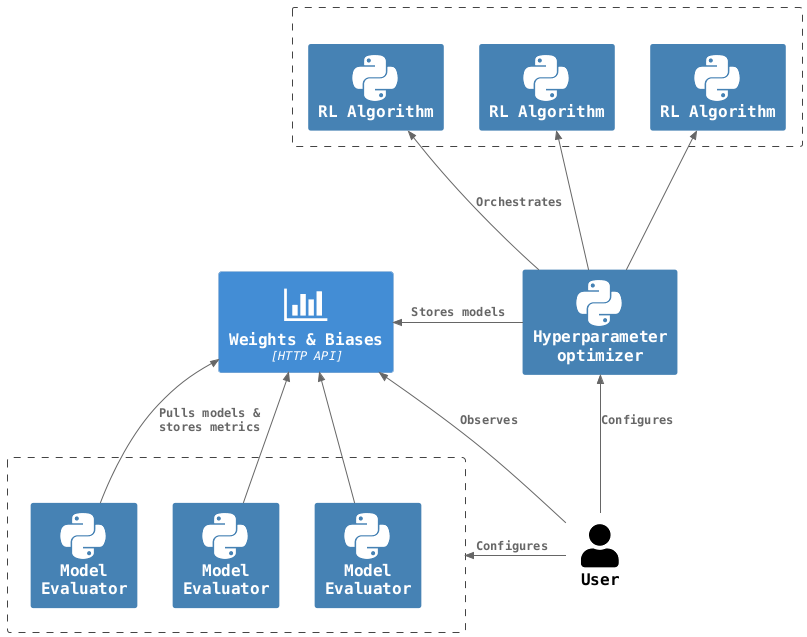

At the time I was training my models on 3 different machines at home (poor man’s RL training cluster), each of which was exporting a new version of the model being trained at regular intervals. I used W&B as a centralized storage (they give you 100GB of storage on the free tier, which is amazing) for models and and designed an evaluator which could work in a distributed manner (i.e. in parallel with other evaluators on different machines), pulling stored models, evaluating their performance and pushing the results. Here’s how it looks:

At regular intervals, the hyperparam optimizer uploads W&B artifacts containing trained models. The evaluators download those models, load them and let them play against multiple types of opponents (StupidAI and BattleAI - the two in-game scripted bots) on several different maps which contain unseen army compositions. The results of those battles are stored for visualisation and the models - marked as evaluated (using W&B artifact tags) to prevent double evaluation.

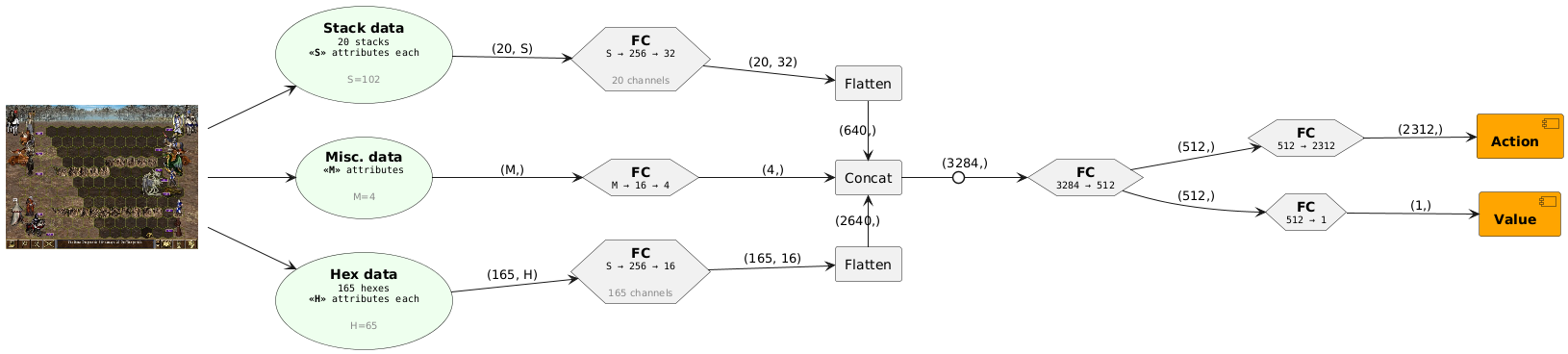

🧠 Neural Network

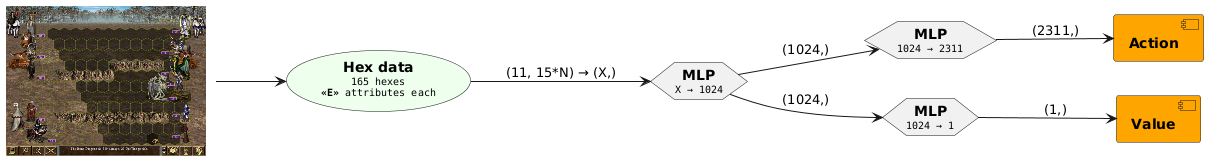

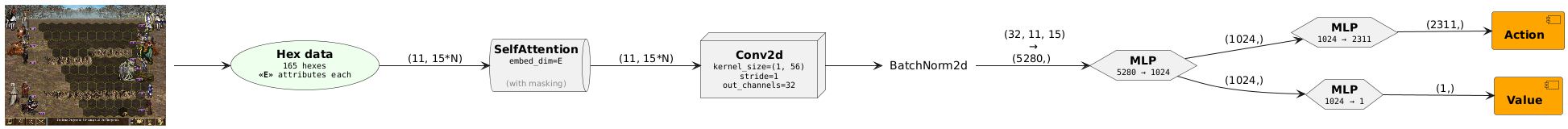

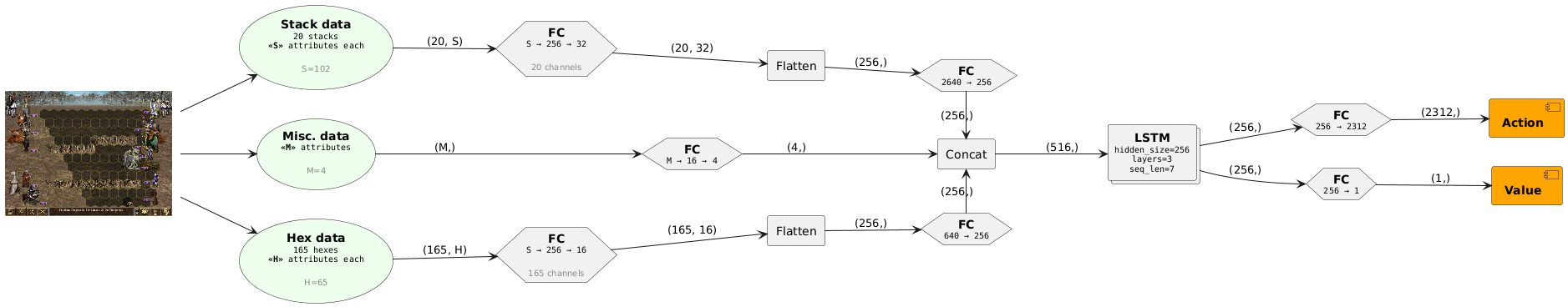

Along with the reward scaling, the thing I experimented the most with was the architectures of the neural network. Various mixtures of fully-connected (FC), convolutional (Conv1d, Conv2d), residual (ResNet), recurrent (LSTM) and self-attention layers were used in this project with varying success. In general, results for NNs which contained SelfAttention and/or LSTM layers were simply worse, so I eventually stopped experimenting with them. Similarly, batch normalization and dropout also seemed to do more harm than good, so those were removed as well.

.

.

.

Fast forward to 2025

It’s been a year now since I’ve last published any updates here. In short, I started a new job at GATE (Big Data for Smart Society Institute) and, most importantly, my son Stefan was born!

Time became a scarce resource. I remained committed to the vcmi-gym/MMAI project and managed to sneak a couple of hours nearly every day, but I did not have the bandwidth to turn that work into coherent updates. In an attempt to catch up, I will summarize what I tried, what failed, what worked, and what finally made MMAI feel like a serious contribution rather than a prototype.

The first MMAI contribution

In October 2024, I submitted MMAI in a pull request to the VCMI repo.

It contained a single model. At that point I had already observed that training two separate policies (one for attacker and one for defender) consistently outperformed a single “universal” policy. Since neutral fights in VCMI always place neutrals on the defender side, the model I shipped was defender-only, and the initial integration allowed choosing MMAI only as the neutral AI.

Key characteristics of the initial submission model:

- Architecture: a small variation of the neural network described earlier.

- Performance:

- ~75% win rate vs. StupidAI (VCMI’s “weak” scripted bot)

- ~45% win rate vs. BattleAI (VCMI’s “strong” scripted bot)

The contribution did not exactly go as planned: there were mixed reactions and it became apparent that there’s more to be desired if MMAI were to become a part of VCMI.

Why the PR stalled

The community feedback was direct, and it was fair. Some of the main issues were:

- Strength: the model was still weaker than BattleAI, so the practical value of merging it was questionable.

- Play experience: it was not enjoyable to play against. It behaved too passively – often backing away and waiting, effectively forcing the human player to engage first.

- Creature bank battlefields: it struggled with the circular/irregular troop placement used in creature banks. In particular, it behaved poorly for stacks in the top-left corner because it had almost never been trained on those layouts. The result looked like a bug, even if the underlying cause was distribution shift.

That seemingly took the steam out of this contribution, so instead of pushing for the merge, I took a step back to see what can be improved.

Back to the drawing board

I iterated across several axes at once:

- different NN architectures

- different RL algorithms

- different observation and action spaces

- different reward functions

Some of these paths ended up being expensive lessons.

Iterations took days, sometimes weeks, and experiments were effectively sequential. I had to step-up my game: I moved from local hardware to rented GPUs on VastAI, and migrated long-term storage to AWS S3. That improved iteration speed dramatically.

I also reworked the sampling/training pipeline: instead of many independent PBT workers each running their own small workload, I leaned into gymnasium vector environments (with a patch to make VCMI play nicely) so that inference and learning could run in larger batches and the GPU would stop idling. That enabled me to more freely carry out the experminets that followed.

DreamerV3

Significant effort, zero learning.

I spent a substatial amount of time trying to make DreamerV3 work, using:

- a modified ray[tune] setup, and

- SheepRL’s implementation adapted for masked action spaces.

Despite eventually getting the training pipeline running, the models simply did not learn. Not “learned slowly” - they failed to learn even basic competence across the hyperparameter space I tried. I never found the root cause, and at some point continuing to push here stopped being rational. I dropped DreamerV3 and decided to move on. At least I had managed to submit several Ray bug fixes along the way.

MCTS (AlphaZero/MuZero family)

Attractive in theory, impractical in VCMI.

For turn-based, adversarial, positional games, MCTS-style approaches (AlphaZero, MuZero, etc.) are a natural temptation. The problem is structural: to do tree search, you need an environment that can branch:

- step forward N actions,

- roll back,

- step forward N different actions,

- roll back again,

- repeat.

VCMI battles are not designed to “rewind” cleanly. Rolling back the last N actions reliably is a non-trivial engineering project on its own. I noticed there’s a fellow AI enthusiast on the VCMI discord channel who is working on an MCTS-based AI model, hopefully he will be able to overcome this limitation.

Instead, I decided to explore the alternative: train a model that can simulate battle progression.

Simulation models

Simulating sequences of turns in VCMI battles requires two capabilities:

- State transitions (what the world becomes after an action)

- Opponent behavior (what the enemy does in a given state)

Those are distinct problems, so I trained two models:

- Transition model (codename

t10n):- input: (battlefield_state, chosen_action)

- output: predicted_next_state

- Policy/prediction model (codename

p10n):- input: battlefield_state

- output: predicted_action (e.g. what BattleAI would do)

How one imagined “timestep” works

Assume it is our turn as the model, playing as defender. We want to evaluate action X without executing it in VCMI.

Pseudo-code:

state = obs

action = candidate_action

# roll forward until the turn comes back to us

while True:

next_state = t10n(state, action)

if next_state.side_to_act == "us":

break

action = p10n(next_state) # predict opponent response state = next_state

return next_state

Once a single timestep can be imagined like this, imagining a horizon-H trajectory is just a matter of repeating the above loop H times.

Training the simulation models

Unlike online RL, training t10n and p10n is essentially supervised learning on logged transitions:

-

t10ntraining pairs: (state, action) → next_state -

p10ntraining pairs: state → action

That decoupling is convenient because it allows offline data collection, but it comes at a cost: data volume.

A single sample (two observations + one action) was ~100KB. At that size:

- 1M samples ≈ 100GB

- “millions” of samples quickly becomes terabytes

Two immediate bottlenecks followed:

- Storage cost: not only S3, but also VM storage (VastAI charges you per GB of storage used).

- Transfer time: repeatedly downloading terabytes of data is slow and costly (VastAI charges per GB downloaded, as well as a fixed charge for renting the VM)

Fortunately, NumPy’s built-in compressed storage reduced sample size by roughly 10×–20×. That made the dataset manageable, at the price of CPU overhead for (de)compression—which was acceptable compared to the storage and transfer costs.

With vectorized environments, PyTorch data loaders, and a custom packing format, I eventually collected millions of samples and had enough data to train both models.

Loss functions

Easy for p10n, non-trivial for t10n.

For p10n, the output is an action distribution, and the target is a one-hot action. Standard cross-entropy works well.

For t10n, the state contains a mixture of feature types:

- Continuous (e.g. HP normalized to [0,1])

- Binary (e.g. traits/flags)

- Categorical (e.g. slot IDs, unit types, etc.)

A single MSE loss is a poor fit. Instead I used a composite objective:

- MSE for continuous

- BCE for binary

- CE for categorical

Conceptually:

L = mse(continuous) + bce(binary) + ce(categorical)

After a couple of months of training and iteration I had a t10n and p10n pair that looked promising.

Handling simulation uncertainty

The first time I tried to render t10n’s predicted output, it became obvious that post-processing was required.

t10n outputs probabilities, not discrete game states. For binary values, that means outputs like 0.93 instead of 1. This is not necessarily wrong: some transitions are genuinely stochastic (e.g. paralysis chance). The model reflects that uncertainty.

To render a state, however, VCMI needs discrete values, i.e. you can’t render a “70%” paralyzed creature - it must be either paralyzed or not. So, the predicted state has to be collapsed into a concrete instance:

- binary flags snapped to 0/1

- categorical logits turned into an argmax category

- constraints enforced so that invalid combinations do not survive

With this, a probabalistic state could be materialized into concrete instances.

The “world model”

Usable, but not stable enough for serious MCTS.

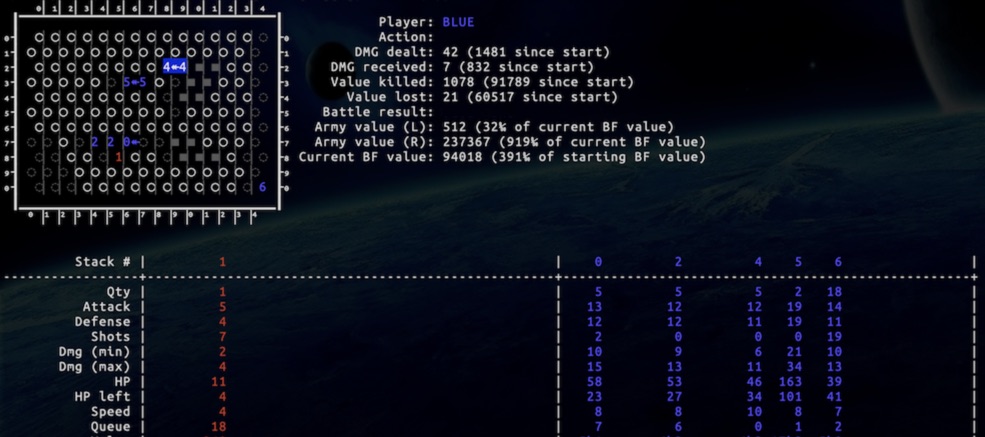

Combining t10n and p10n gave me a “world model” capable of imagining future rollouts.

A rollout is a sequence of timesteps, which in turn are sequences of transitions.

The world model is capable of simulating only transitions, hence timesteps and rollouts must be generated in an autoregressive manner. This naturally leads to a fundamental problem: autoregressive error accumulation. It manifests as innacuracies and hallucinations, resulting in invalid states. For example, a unit which may have been paralyzed would mean its “paralyze” flag (which should be either 1 or 0) is a superposition of both states, e.g. 0.4. There is no such thing as a “40% paralyzed creature” in VCMI - it’s either paralyzed or not.

To contain this, I collapsed states after every transition and fed the collapsed versions forward. Collapsing is a term borrowed from quantum mechanics. You can think of it as rounding in the case of numeric data. For categoricals, this eliminated many reconstruction failures, but it also exposed the model’s hallucinations more clearly:

- some long exchanges caused excessive drift

- units sometimes morphed into “hybrids” (e.g. a First Aid Tent drifting toward a Dendroid Guard-like unit)

- end-of-battle uncertainty was particularly destructive (once the model becomes unsure the battle ended, it becomes unsure about everything after)

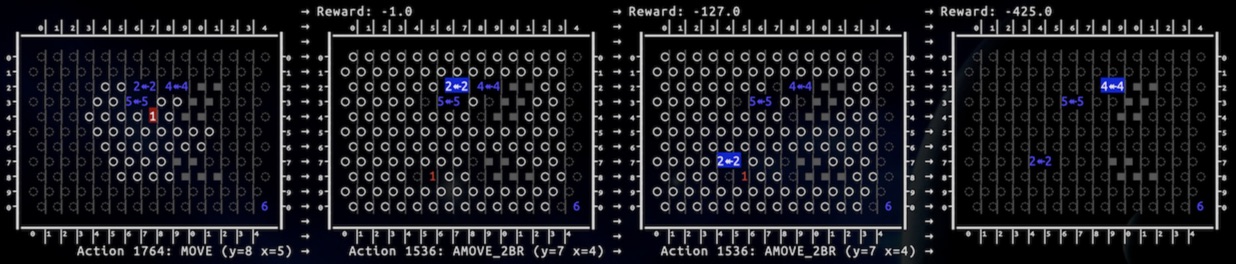

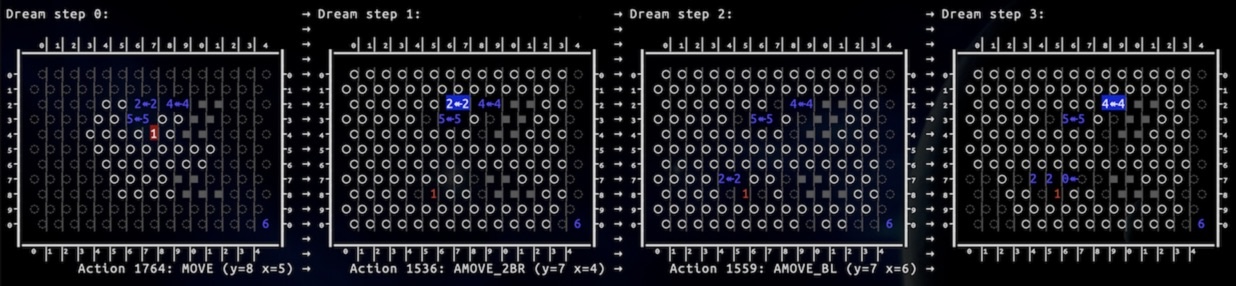

This is best illustrated by comparing the model’s imagined transition sequence (I call it the dream) against the actual transitions occurring in the environment:

Note: Blue units 2 (Pegasus), 4 (Pegasus) and 5 (Death Knight) are wide units and occupy two hexes, marked as 2←2, 4←4 and 5←5.

In this test, we play as red, while VCMI’s BattleAI bot plays as blue.

The actual in-game transitions are as follows:

- Initial condition:

- red unit 1 is active

- the next action is: move to y=8 x=5.

- First transition:

- blue unit 2 is active

- the next action is: attack-move to hex y=7 x=4, striking at red unit 1.

- Second transition:

- blue unit 2 is active again (perhaps it has waited earlier)

- the next action is: attack-move to hex y=7 x=4, striking at red unit 1 (again)

- Third transition:

- red unit 1 was killed.

- battle has ended.

Comparing this against the world model’s dream (imagined transitions):

- Initial condition: same as above.

- First imagined transition: also same as above. The world model has correctly simulated this transition by simulating a new state given the previous state + action, as well as predicting the enemy’s next action.

- Second imagined transition: a distorted version of the actual state:

- a phantom blue unit is active (it’s not visible on the map).

- the predicted action is: attack-move to y=7 x=6, striking at red unit 1. This is no longer the same as the actual transition, but it’s close (apparently, the model becomes uncertain when the same unit has to act twice).

- Third imagined transition: an even blurrier version of the actual state:

- the phantom unit has materialized as blue unit 0←. The arrow indicates this is a wide unit (occupying 2 hexes), but its second hex is marked “unreachable” (dark circle).

- red unit 1 was not killed.

- the battle has not ended.

- blue unit 4 is active.

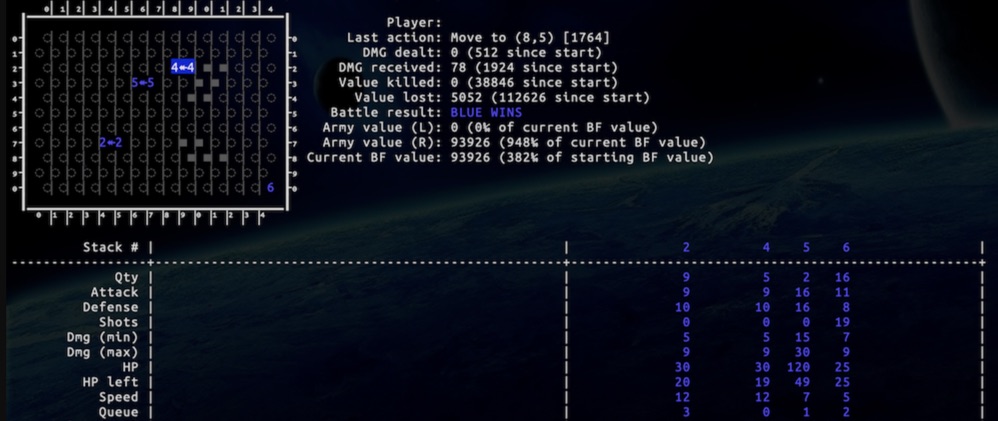

In this dream, the battle continues. The imagined states have become disconnected from the actual ones. Looking at the creatures’ stats, we can see a numerical drift as well:

Comparing the actual vs imagined stats:

- There is a noticeable drift, although some similarity remains. Looking carefully, you will notice that creatures in the dream appear more powerful than they actually are - an interesting topic on its own.

- The phantom unit (blue unit 0) is very similar to blue unit 2. As if unit 2 was split in two, preserving the overall strength of the blue army and resulting in one extra unit.

- The still alive red unit 1 has barely survived and will not act for another 17 rounds (Queue=18) - a clear signal that the model is uncertain if the unit is dead or alive.

This shows how the imagined states deeper in the dream drift further away from reality. Not surprising, but I find it oddly satisfying to observe. Unfortunately, such a model is not a viable replacement for the VCMI game engine for the purposes of MCTS, which requires a much more faithful simulator. With no mature open-source MuZero-like stack I could practically adapt, the expected return on further investment dropped sharply.

I did try muax because it is referenced from DeepMind’s mctx ecosystem, but it turned out to be a thin wrapper around assumptions that did not fit my use case (no batching/vectorization, no support for GPU computation, strong constraints on observation/action types, etc.). The timing was unfortunate — I found these constraints late, but the detour was still useful: I learned to write JAX by rewriting my models in JAX/Flax, then rewriting them again for Haiku. It was an instructive exercise and I would definitely keep Jax in mind for my future projects, but it did not unlock MCTS.

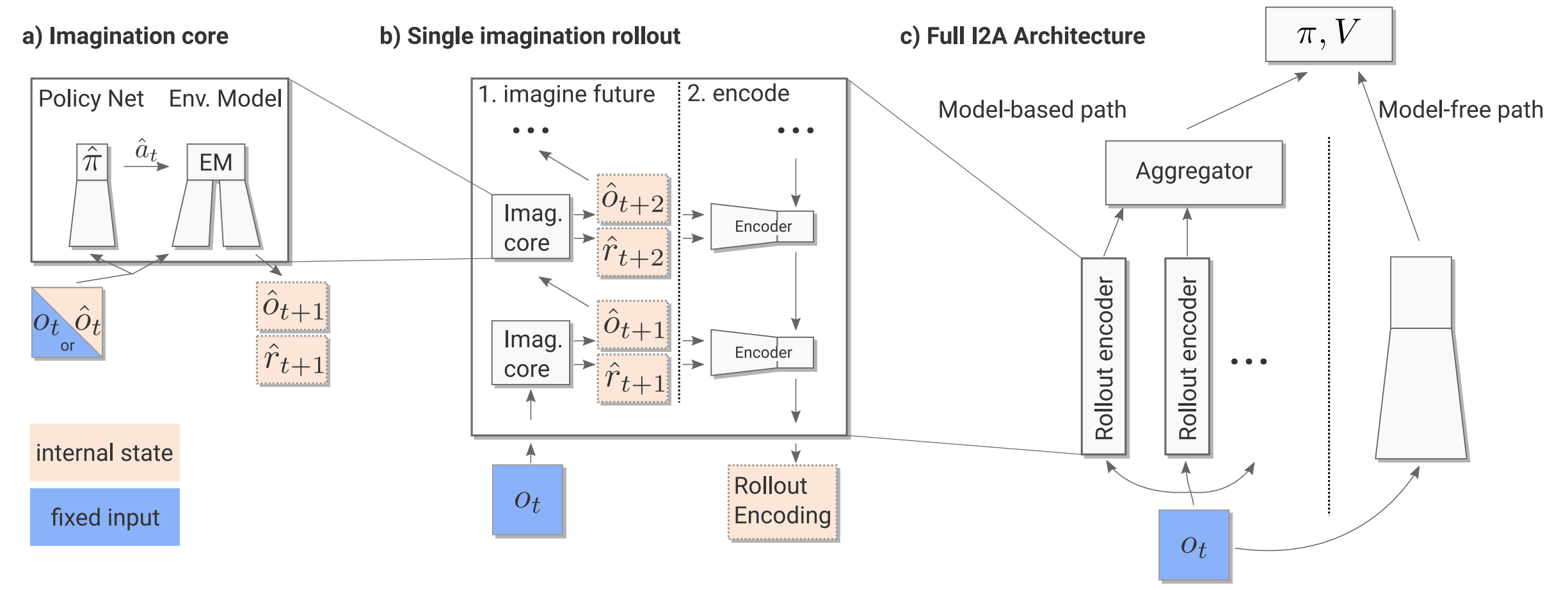

At that point, I pivoted to a different imagination-based idea: I2A.

The I2A model

I2A (Imagination-Augmented Agents), introduced in a research paper from 2017, integrates a learned world model into an otherwise model-free policy by adding an “imagination core” that generates rollouts, which the policy learns to interpret. The key claim that caught my attention: I2A can still be useful even when the environment model is imperfect.

My t10n + p10n world model looked like a fit. Unfortunately, VCMI’s action space makes this approach computationally brutal.

With:

- horizon = 5 timesteps

- trajectories = 10

- batch_size = 10 steps

…the number of forward passes exploded exponentially (including a third reward model, omitted here for brevity). The overhead was so large that learning slowed to a crawl. Even with aggressive pruning (10 trajectories is well under 30% of the actions a unit can take on average), the compute budget was dominated by “imagination”, not learning.

I2A was not viable for this problem under these constraints.

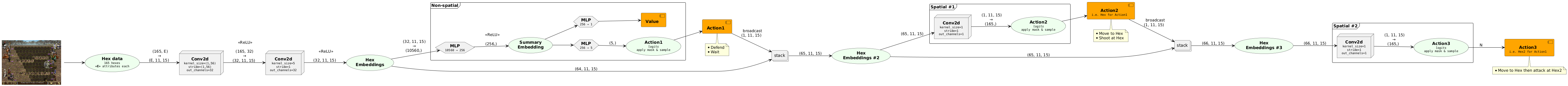

MPPO-DNA model (revised)

The action space is the enemy.

At this point I returned to MPPO-DNA and focused on what repeatedly hurt almost every algorithm I tried:

2312 discrete actions.

I had previously attempted a multi-head policy that decomposes the action into several parts (inspired by “mini-AlphaStar”-style spatial/non-spatial factorization), but that attempt did not converge well. This time I restarted the implementation from scratch to avoid “fixing” myself into the same design.

Hex-aware spatial processing

A major architectural change was implementing a custom 2D convolution-like layer for a hex grid. Standard 2D convolutions assume a square lattice; VCMI battlefields are hex-based. Treating hexes as squares is possible, but it causes geometric distortion.

I designed a hex-convolutional kernel (bottom) to address this issue.

Adding transformers

Incorporating Transformer encoder layers attending over the hexes was the first time I saw models reach ~50% win rate vs BattleAI. The layers added were:

- self-attention (hex ↔ hex)

- cross-attention (global state → hexes)

That was a genuine milestone, but there was a catch: models became unstable.

The slump

Transformer-based models often trained well, but then abruptly collapsed. Lower learning rates, gradient norm clipping and reducing the number of transformer layers were among the first things I tried, but none worked. Collapsing persisted across runs. I still do not have a reasonable explanation.

Still, the direction felt correct: I wanted global context propagation without destroying spatial structure. That led naturally to the next step.

The GNN pivot

Everything can be represented as a graph.

Graph neural networks (GNN) are specialized artificial neural networks that are designed for tasks whose inputs are graphs. GNNs have enjoyed great recognition in the recent years, with DeepMind’s GraphCast (deemed “the most accurate 10-day global weather forecasting system in the world”) and AlphaFold (a 2024 Nobel Price winning protein folding predictor) being notable examples. I decided to explore a GNN-based approach for vcmi-gym, which meant I had to first and foremost find out how to represent the VCMI battlefield as a graph.

Graphs are an amazing way to model information - they excel at modeling objects (called graph nodes), their relationships (called graph edges). Feeding this into a graph neural network (GNN), the processing of the information flow through those edges (called message passing) can be further adapted for efficient learning.

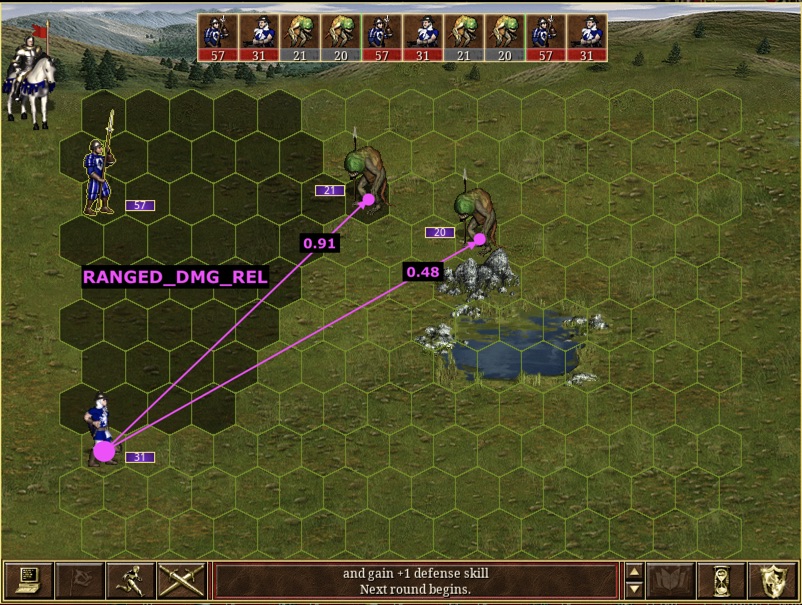

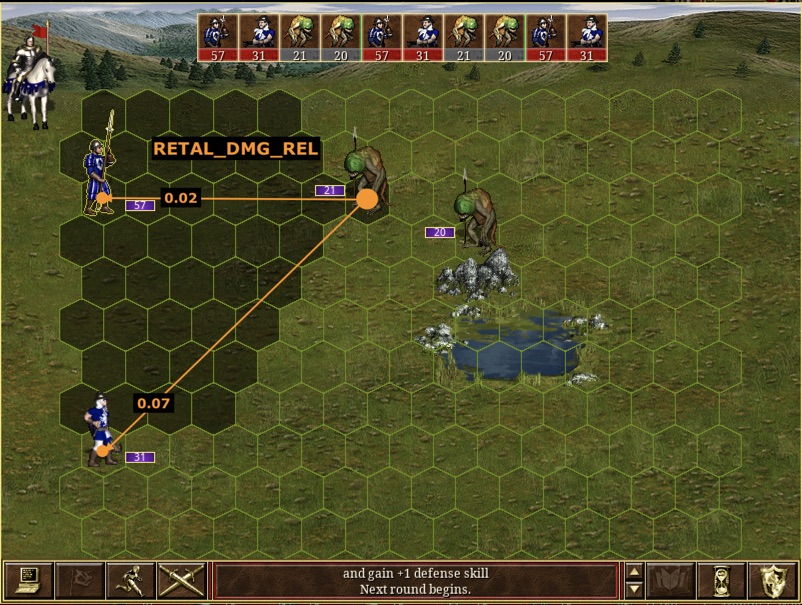

For VCMI I defined a heterogenous graph with a single node type (HEX) and seven edge types. The graph contains a fixed number of nodes (165) and a varying number of edges (depending on the unit composition, position, abilities, etc.):

For readability's sake, only the outgoing edges for exactly one node are drawn (in the real graph, each node has similar outgoing edges).

This representation matched how I reason about the battlefield when playing the game: not as a flat tensor, but as entities and relationships, in particular:

- How much damage can unit X deal to unit Y?

- Can unit X reach hex Y?

- Will unit X act before unit Y?

- etc.

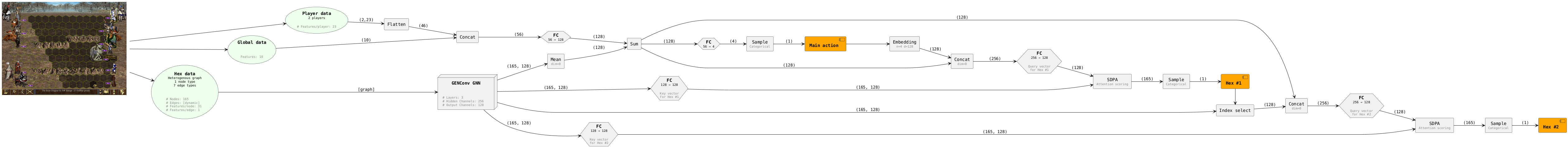

All this required some C++ work and a new MMAI observation version: v12 (yes, by that time, I had reached the 12th iteration), but it worked well. Next up was the neural network design, which governs how this information is processed.

Different GNNs have different message passing logic. Finding a suitable message passing function is not trivial, and sometimes a customised approach is needed. PyTorch Geometric already contains implementations for many of the popular GNNs, so I ran a small suite of experiments across several of them in parallel to see which one would be most promising:

- GCNConv

- GATv2Conv

- TransformerConv

- GINEConv

- PNAConv

- GENConv

I also experimented with various graph design choices along the way:

- static vs dynamic nodes

- directed vs undirected vs bidirectional edges

- homogeneous vs heterogeneous graphs

- different message passing and attention scoring schemes

Some of those experiments delivered promising results. I was on the right track.

The breakthrough

At long last, MMAI supremacy!

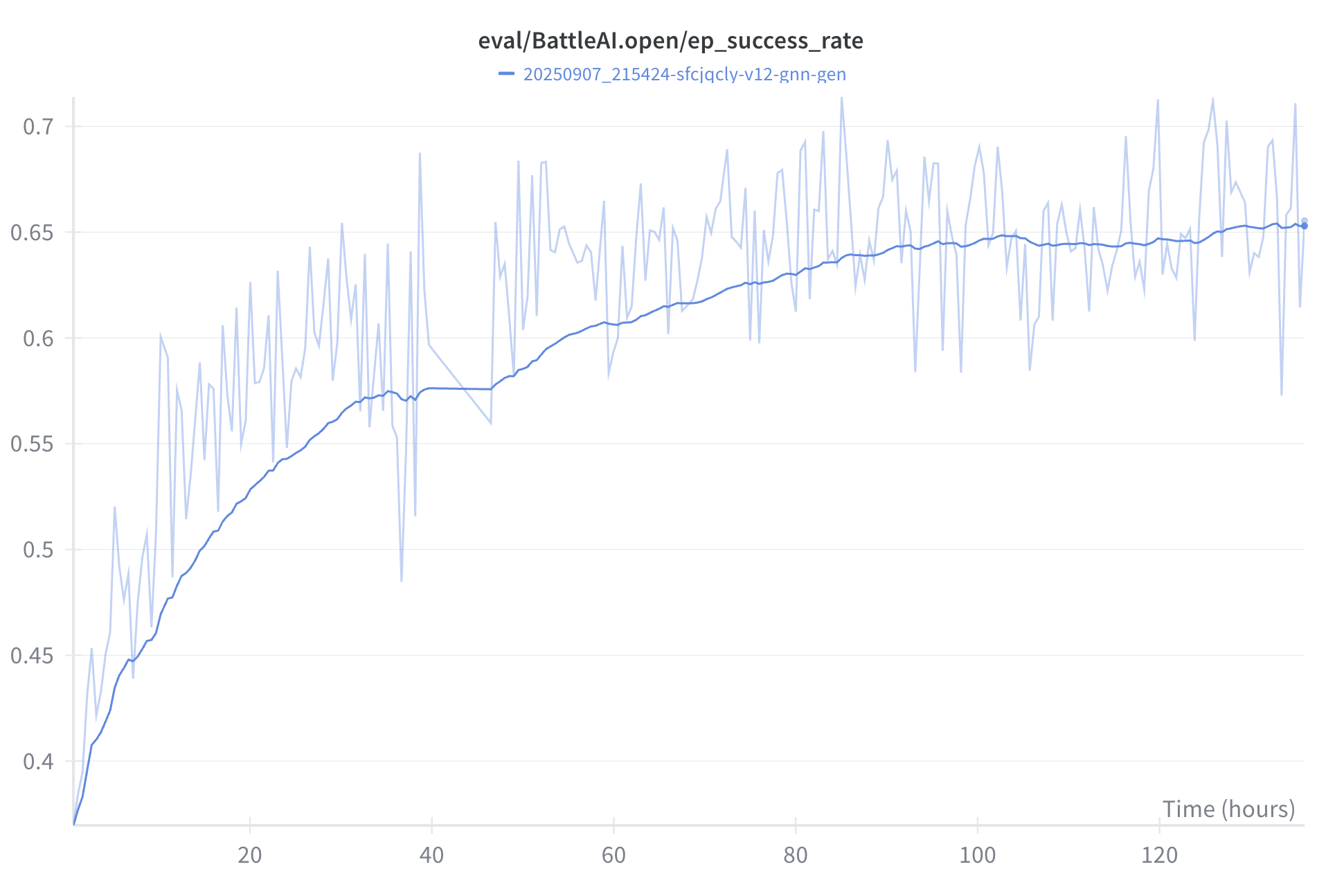

Among the configurations I tried, the GENConv-based models trained on a dynamic heterogeneous graph with directed edges and attention-style scoring seemed to perform best.

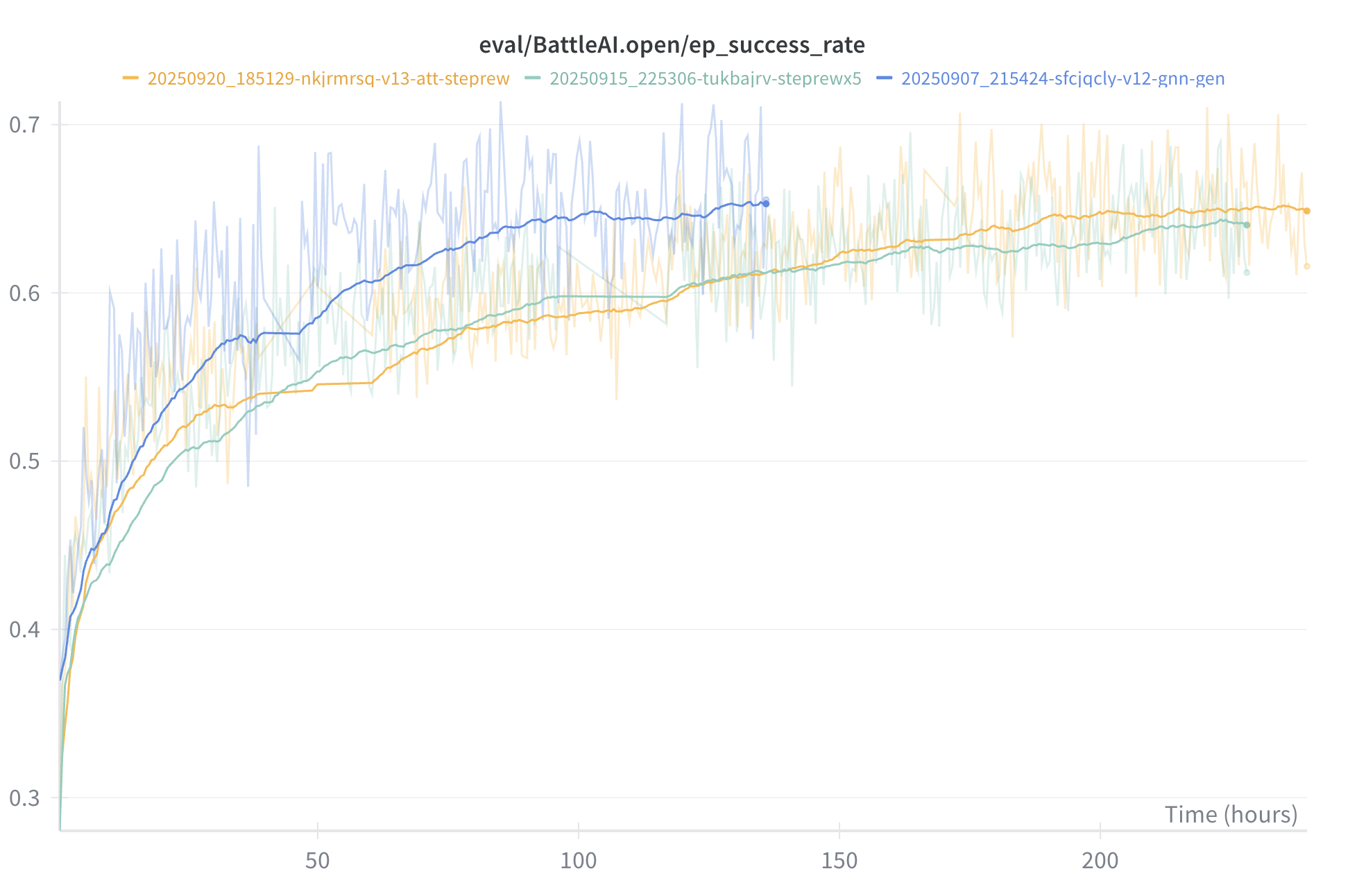

Further experiments based on similar configurations rewarded me with exceptional results: win rates vs. BattleAI climbed to an average of 65%. After a year of “almost there”, this finally felt good.

This was it. Now I wanted to try and play against this model, 1v1, me vs. MMAI! To do it, I first had to find a way to export it from vcmi-gym and then load it in the standalone game.

Exporting the model

The charts were looking great, but it was time to test it out myself. However, it was still a PyTorch Geometric model i.e. just a Python artifact. To load it inside VCMI, I needed a C++ loadable format. TorchScript exports had previously been my path, but PyTorch’s model export for edge devices such as mobile phones has been deprecated in favor of executorch, so I went for it instead.

ExecuTorch: XNNPACK

ExecuTorch supports multiple backends (CoreML, Vulkan, XNNPACK, OpenVINO, etc.). The difficulty is that VCMI targets a wide platform matrix (Windows/Linux/macOS/iOS/Android; multiple architectures), while most backends are platform-specific.

XNNPACK was the only backend that looked plausibly universal. In practice, making the model lowerable to XNNPACK required a heavy redesign due to the limitations imposed by the limited available opset:

- no dynamic shapes

- no “smart” indexing

- softmax/argmax/sampling-style logic had to rewritten with primitive tensor ops (gather/scatter/index_select style)

- PyG structures (HeteroData/HeteroBatch) had to be replaced by flat, fixed-shape tensors

-

infmasks had to be replaced with large finite negatives

In addition, the fixed-size limitation meant that dynamic graphs were not an option, so support for several different fixed sizes (buckets) was added to avoid wasting compute (the appropriate bucket is chosen at runtime based on the graph size). A fixed-size graph would always contain the same amount of nodes and edges and by choosing the appropriate bucket container, the amount of padding is kept at a minimum.

As an example, let’s imagine a battlefield with only 100 edges: if the graph size is fixed at 500 edges, the model would expect 500 edges in its input, meaning we need to zero-pad the “missing” ones, ending up with 400 “null” edges. The model then performs all tensor operations in the neural network on all 500 edges, effectively wasting 80% of the compute on edges which don’t exist. A bucketed approach means pre-defining several fixed sizes that the model can work with, then choosing the appropriate size at runtime - following this example, I could define buckets for S=50, M=150, L=300, XL=500 edges and choose the bucket M for representing the given example battlefield.

The bucket definitions were guided by size statistics collected over ~10,000 observations:

Number of edges E (total on battlefield) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edge type | max | p99 | p90 | p75 | p50 | p25 |

ADJACENT | 888 | 888 | 888 | 888 | 888 | 888 |

REACH | 988 | 820 | 614 | 478 | 329 | 209 |

RANGED_MOD | 2403 | 1285 | 646 | 483 | 322 | 162 |

ACTS_BEFORE | 268 | 203 | 118 | 75 | 35 | 15 |

MELEE_DMG_REL | 198 | 160 | 103 | 60 | 31 | 14 |

RETAL_DMG_REL | 165 | 113 | 67 | 38 | 18 | 8 |

RANGED_DMG_REL | 133 | 60 | 29 | 18 | 9 | 4 |

Max number of inbound edges K (per hex) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edge type | max | p99 | p90 | p75 | p50 | p25 |

ADJACENT | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

REACH | 13 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 3 |

RANGED_MOD | 15 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

ACTS_BEFORE | 23 | 19 | 15 | 12 | 8 | 5 |

MELEE_DMG_REL | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 3 |

RETAL_DMG_REL | 10 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 3 |

RANGED_DMG_REL | 8 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

Based on this information, I defined 6 graph buckets (starting from the rightmost column, going left): S, M, L, XL, XXL and MAX.

But even with the bucketed approach, the XNNPACK model was still slow to respond: 700ms (for bucket M) is not acceptable during gameplay. Imagine a single-player game with 6 computer players, each of which fights one or more battles during their turn(each battle involves at least 10 predictions) - that’s 30+ seconds, and if you’ve ever played HOMM3, you know that computer turns should be much faster than that (usually less than 5-10 seconds in total).

Additionally, I ran into platform/toolchain issues and memory violation errors on Windows. I spend considerable amount of time fixing that, but given that Executorch’s support for Linux, Windows and MacOS still only an experimental feature, eventually decided to give it up. I needed a different deployment strategy.

In the end, even though I had put considerable amount of time into the XNNPACK export, it was still worth it as I gained a solid understanding of the GNN implementation internals. The bucketed approach for lowering the graph dimensionality was backend-agnostic and would also come in handy later.

ExecuTorch: Vulkan and CoreML

I explored Vulkan and CoreML exports to see if those would bring a viable performance improvement, but stumbled upon many problems:

- Vulkan had instability and platform build issues and the C++ code ultimately failed to load models on android devices due to a cryptic shader-related error.

- CoreML displayed good runtime performance on Apple devices, but the CoreML models were several times larger in size and the very first forward pass of those models took a whopping 10 seconds on iOS which felt pretty bad.

Neither was a good solution, there had to be a better way.

Libtorch (revised)

I returned to libtorch. Compiling it from source is painful, so I built it separately and consumed it as an external library in VCMI.

Libtorch had its drawbacks (such as large library size), but it was performing well and was more portable compared to ExecuTorch. I decided to go for it, and I updated the MMAI pull request accordingly.

ONNX

During the PR review phase, @Laserlicht suggested I should replace libtorch with ONNX Runtime because it has solid packaging support and broad platform coverage. Having spent so much effort to replace libtorch with ExecuTorch, I was not exactly eager to try yet another alternative to libtorch, but the suggestion did seem reasonable, so it was worth a try.

In a last-ditch effort to find a well-performaning solution with multi-platform support, I exported the MMAI models as ONNX graphs. The size footprint was small (as small as it could get with 11 million parameters, which is around 20MB). It was also relatively easy to wire it up in VCMI, but most notable, the inference benchmarks were surprising: ONNX models were ~30% faster than their libtorch counterparts. It was enough for me, given it also provided overall smoother integration experience.

With help from @GeorgeK1ng, we also managed to produce working 32-bit Windows artifacts for the integration. This meant VCMI’s entire build matrix (a total of 16 different builds) is now buildable with MMAI support thanks to ONNX runtime!

| Model Format | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| TorchScript |

|

|

| ExecuTorch: XNNPACK |

|

|

| ExecuTorch: Vulkan |

| |

| ExecuTorch: CoreML |

|

|

| ONNX Runtime |

|

|

NOTE: the inference values are results from my own mini-benchmark on 3 different devices: Mac M1 / iPhone 2020SE / Samsung Galaxy A71

Playtesting

With libtorch set up, I could finally play the game vs my new model :) I quickly noticed a worrying sign:

Even though the model played well, it had one persistent behavioral flaw: it was still too defensive — often waiting for enemies to step within range, sometimes even running away, instead of proactively making attacks.

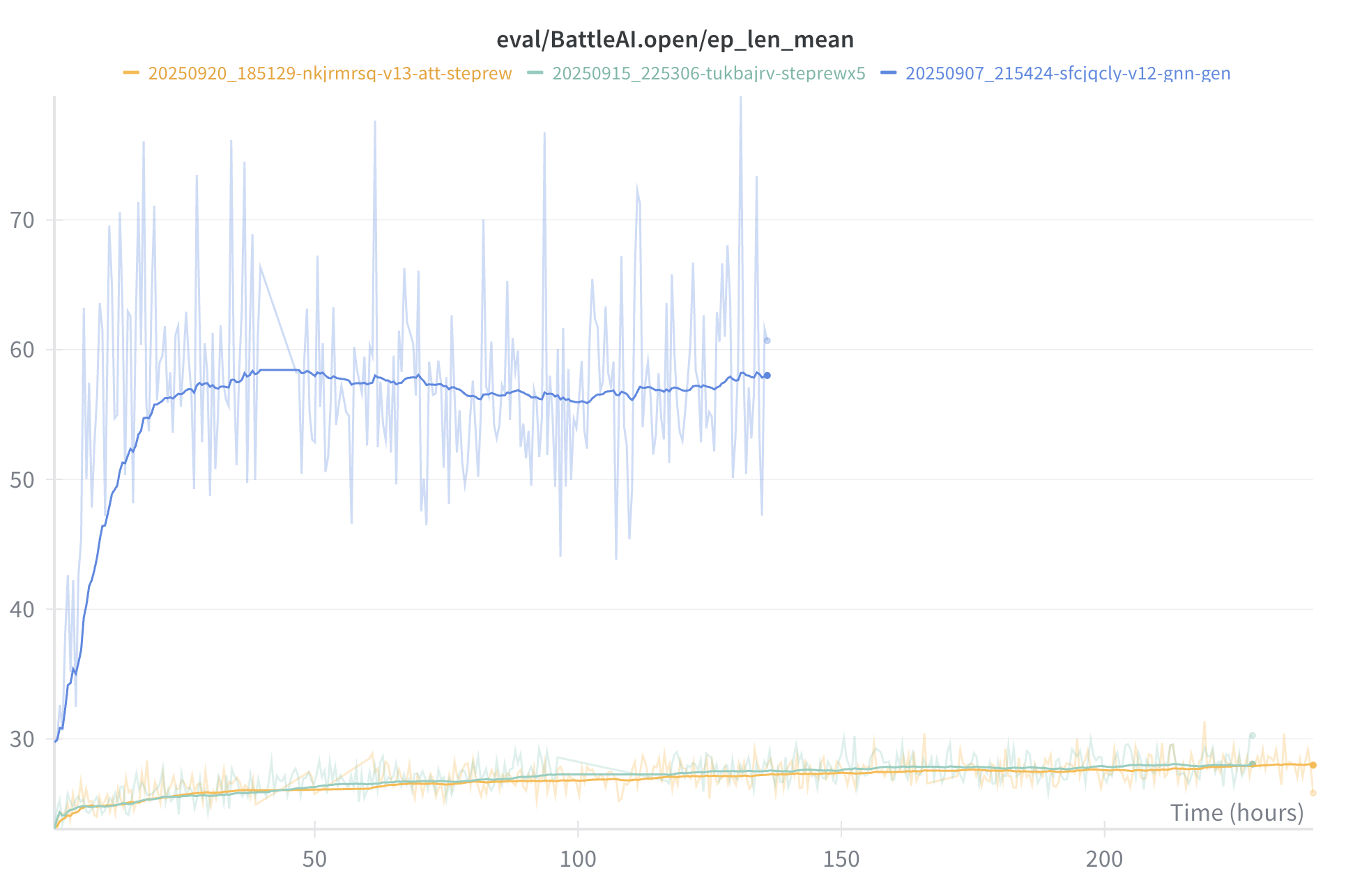

This in particular was one of the early PR criticisms, so I treated it as a blocker and started looking for ways to fix it. I went with the simplest approach I could think of - a fixed, negative per-step reward - and it worked well: at the expense of a small drop in win rate vs BattleAI, I managed to greatly reduce the episode duration (i.e. number of turns in battle):

Going on with the manual playthrough, I was pleased to find out that MMAI had learned a handful of important tactical moves, such as:

- actively trying to block enemy shooters

- not attacking “sleeping” units (paralyzed, petrified, etc.) to avoid waking them up

- repositioning its own blocked shooters instead of using their weak melee attack

- staying out of enemy shooters’ range, for the first few rounds at least

On the other hand, on some occasions it was still making bad decisions, although such occurred rarely now:

- may still play too defensively, waiting for the enemy to attack first, never taking the initiative

- may take “baits”, attacking cheap enemy units thrown forward, exposing its own

- may fail to recognize dead ends on battlefields where the randomly placed terrain obstacles form “blind alleys”

Nonetheless, my overall assessment was positive – MMAI played reasonably well. Better than the bots, still not better than a human, but a worthy first-generation model for ML-powered AI in VCMI.

The merge

In late 2025 (more than a year after the PR was initially opened), I posted an update with my new MMAI v13 models. This sparked new discussions, suggestions, code reviews and improvements and, at last - a merge.

MMAI was officially released with VCMI-1.7!

This means it will finally see proper playtesting from human players. I have been collecting gameplay feedback from early testers in the VCMI community, and I expect much more to follow. Sadly, the feedback has been mostly negative so far :( Players seem to have rather high expectations, reporting the model’s bad decisions (such as the ones I outlined above) as issues to be fixed. Easier said than done, but they’re being honest and I value that.

My working theory is that the LLM boom in recent years has raised the AI bar to an extent where people take human-like AI behaviour as a baseline. LLMs and RL agents are fundamentally different and while transformers brought a revolution for all language models, we are yet to see a similar breaktrhough in reinforcement learning. Until then, comparing RL agents to LLMs is not a fair matchup. That being said, I know the criticism will be useful for the upcoming generations of new MMAI models, and I already have a few ideas in mind for the next versions. Stay tuned :)